By Bob Hall

In early 1970, Malcolm Fraser, then Minister for Defence in the Gorton-led Coalition government, visited Vietnam to ‘survey the political situation, the prospects of the Saigon Government, and the progress in pacification of the countryside’.[1] According to the Departmental Secretary, Arthur Tange, Fraser was dissatisfied with what he saw. In particular Fraser believed that reporting from Saigon through military and embassy channels was fragmented and inadequate. In discussions with the Australian Ambassador in Saigon, Ralph.L. Harry, Fraser decided that the Australian Joint Intelligence Organisation (JIO) was to produce a monthly report on the general situation in Phuoc Tuy Province. The report was to cover the military, security, economic and social aspects of the campaign.[2]

Ambassador Harry pointed out that the Embassy and HQ Australian Force Vietnam (AFV) had already established a monthly committee meeting to examine the pacification situation in Phuoc Tuy Province. These monthly Pacification meetings began in May 1969 and produced reports which were distributed to the Departments of Defence and External Affairs in Canberra. The monthly Pacification meetings comprised representatives from the Embassy, Headquarters AFV and Headquarters 1ATF. Discussions were based on the monthly report of the American Province Senior Adviser, the report of the Australian Civic Action Group and on briefings by senior officers of the Australian Task Force as well as other available information. The reports provided a comprehensive review of the situation, month by month, affecting Australian operations in Vietnam. Harry suggested that the Pacification committee’s monthly reports could be used as the basis for the reports required by Defence Minister Fraser from JIO.[3]

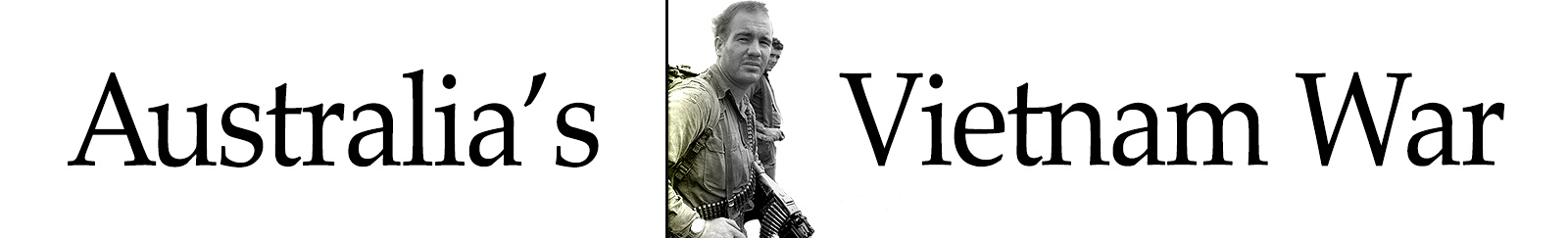

Minister for Defence, Malcolm Fraser is greeted by the Chairman, Free World Military Assistance Organisation, Lieutenant General Tran Ngoc Tam on Fraser’s arrival at Tan Son Nhut airport in April 1970. Behind Fraser and General Tran is Major General C.A.E. Fraser, Commander, Australian Force Vietnam. To the left is General Sir John Wilton, Chairman of the Australian Chiefs of Staff Committee, shaking hands with the Australian Ambassador to South Vietnam, Ralph Harry. (AWM WAR/70/0191/VN)

By June 1970 Fraser’s reporting system had still not been put in place. The Department of External Affairs was concerned that the report should convey an Australian view of the whole campaign hidden behind a focus on the Australian Area of Operations; Phuoc Tuy Province. External Affairs informed the Embassy in Saigon that

We are anxious that the existence of the monthly report should not become known to the U.S. or South Vietnam. For this reason it is considered to be important that the maximum information and assessment be included on the situation in Phuoc Tuy Province. Nevertheless, the aim of the paper is to report on the situation in all of South Vietnam; consequently where possible trends and developments in Phuoc Tuy will be shown within or against the situation in the remainder of South Vietnam.[4]

The first of the NIC reports, covering May 1970, was published as NIC note number 2/70 on 2 July 1970.[5] The concern to create a reporting system covering the whole of South Vietnam but independent of U.S. or South Vietnamese influence suggests that, by mid-1970, Foreign Affairs and Defence had developed a sceptical view of reports they received from those sources and were seeking a more realistic assessment.

The 2 July report covered the period in which US and South Vietnamese forces began operations into Cambodia. The NIC report noted:

It is not yet possible to assess the longer-term effects of the Cambodian operations on the enemy. The immediate effect in South Vietnam, however, has not been great, since the North Vietnamese main-force units in the Cambodian border sanctuaries that were directly affected have been largely inactive, other than in II Corps, over the last 12 months.[6]

The NIC assessed that the enemy’s loss of supplies could affect enemy operations in III and IV Corps Tactical Zones (CTZ) but this effect had not been felt in May at the time of the report. In I and II CTZ, well to the north of the Cambodian incursion and near North Vietnam, enemy activity remained largely unaffected.

True to the promises he had made during his election campaign, President Nixon began the unilateral withdrawal of US forces from Vietnam in June 1969. These withdrawals raised concerns about the ability of the Republic of Vietnam’s Armed Forces (RVNAF) to hold off the People’s Army of Vietnam (or North Vietnamese Army). The success of the Cambodian operations had given a boost to South Vietnamese confidence which, the NIC reported, ‘had been affected somewhat by the troop reductions that had already taken place and by the further programme announced by President Nixon in April.’[7] The report felt it was too early to say what difference this upsurge in confidence might have on South Vietnamese forces but regular forces had displayed increasing effectiveness in combat. However, it was likely that their inadequacies would become increasingly important from the beginning of the next round of US and allied withdrawals in October 1970 as the withdrawals bit deeper into US combat power.

According to the report rural pacification had steadily expanded since the major enemy reverses of the Tet offensive of 1968. However, the durability of these changes remained to be tested after the withdrawal of US and allied forces. The NIC reported that Viet Cong infrastructure (VCI) was still largely intact in most areas. VCI strength throughout South Vietnam was estimated at between 70 and 80,000. But the report noted ‘the South Vietnamese show little inclination to grapple with the problem … It remains the biggest single long-term problem facing the Government’.[8]

Another concern addressed by the report was the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES). This consisted of regular monthly surveys of the security of South Vietnam’s approximately 12,600 hamlets and the allocation of a letter denoting each hamlet’s security status; ‘A’ signifying a village under government control, to ‘E’ signifying a village under VC control. Although the Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) was improved in 1970 the NIC report believed it ‘still gives an unrealistically optimistic picture of rural security.’[9] The claim that 79.4 percent of Phuoc Tuy Province hamlets were ‘relatively secure’ was ‘probably somewhat inflated’.

The NIC report took a much more cautious approach to the assessment of village security based on the Australian experience in Phuoc Tuy Province. It stated that:

our assessment … is that the whole process of the ebb and flow of loyalty to the government under conditions of insurgency does not lend itself to computer assessment. Despite considerable efforts to minimize the problems of assessment the basis of the HES is essentially still the subjective judgement of a district or province level adviser. The categories A, B and C generally described as “relatively secure” do not, at least in Phuoc Tuy, accurately depict the substantial freedom of movement of VC forces into these villages and the continued presence of VCI within them.[10]

Yet while Australians could scorn ‘computer assessment’ in Phuoc Tuy Province with its 150 hamlets, HQ U.S. Military Assistance Command needed a system capable of making sense of the security status of more than 12,000 hamlets. It is not surprising they turned to ‘computer assessment’. Nevertheless, the NIC thought that the broad trend in favour of the government was accurate although the improvement in some areas was assessed as ‘fragile’.

Review of the military situation

This being its first report, the NIC reviewed the military situation in Phuoc Tuy Province. It stated that on its arrival in Phuoc Tuy in 1966 the Australian Task Force was faced with a very serious situation. The Province had long been a VC stronghold, serving as a food-collection and recruitment area and a resupply route from the coast. South Vietnamese Government forces had made little attempt to bring the population under government control. In addition to the local VC political infrastructure (VCI) there were either based on the province or operating in it, 5 VC Division of two regiments, one provincial battalion and three district units. During 1966 and until June 1967, 1ATF constantly confronted these major units and from time to time clashed with them. The major objective of 1ATF operations during this period was to protect the populated areas of the province from the main-force regiments so that the task of pacification could proceed. With the move out of Phuoc Tuy of the headquarters of 5 VC Division and its 275 Regiment, and the subsequent inactivity in relation to Phuoc Tuy of 274 Regiment (which remained in the area), 1ATF had for the first time been able to devote a major part of its effort to dealing with the district and provincial VC forces. The continuing threat in Phuoc Tuy was therefore from these forces and the local VC infrastructure, which constituted a much more elusive and difficult target than the more easily recognizable main-force units. However, an increased main-force threat could be launched against the province at short notice.

The report noted that enemy combat strengths as of May 1970 were difficult to assess but were probably 1,830 main-force, 495 local-force and 350 guerrillas giving a total of 2,675. Local VC units continued to operate in ‘small, dispersed groups; the largest VC force contacted by 1ATF was between 30 and 40 strong.’[11]

Vietnamisation

The NIC report defined Vietnamisation as the policy of developing the capability of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF) to the point where it could assume progressively the responsibility for tasks previously undertaken by U.S. and allied forces. It was somewhat critical of the U.S. assessment of Vietnamisation noting that:

In general, although there has been a significant increase in capability, the strengthening of RVNAF is not progressing as soundly and rapidly as is publicly claimed by United States reports.[12]

Nevertheless, ARVN had progressed from being an army on the verge of defeat (in 1965) to one that could take part effectively in the Cambodia operations. However, ARVN was still plagued by major problems including uneven quality, sometimes poor leadership, poor logistics and other support. This was not surprising. From a strength of about half a million men and women in 1965, the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF) had expanded to about 900,000 by mid-1970. This massive expansion was bound to produce patchy combat performance and leadership, training and logistic problems. Nevertheless, the RVNAF capability was trending in the right direction.

Phuoc Tuy

Following these broader assessments, the report turned specifically to Phuoc Tuy. It began by noting that there were no ARVN infantry units in the Province.

On economic and social developments in Phuoc Tuy Province the report said:

There seems to be steady improvement in the economic and political fields in Phuoc Tuy, but the security situation has fluctuated. The significant areas in which little apparent progress has been made are the strengthening of the RF/PF and the reduction of the VCI. 1ATF with its limited resources provides the security behind which improvements in Phuoc Tuy are being achieved. When a significant reduction of the Australian force in the province occurs, as happened temporarily in February 1969, a rapid decline in security results.

Security of villages in Phuoc Tuy, as measured by the U.S. Hamlet Evaluation System (HES) was over-optimistic if taken literally although broad trends in village security appeared to be valid. The report noted that although many hamlets within the province were rated as ‘relatively secure’ or ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ category hamlets, ‘Viet Cong cadres move in and out of them with relative freedom’.[13] The security status of particular villages could change dramatically over a 24-hour period. The report noted that when clashes occurred between the Regional Force/Popular Force (RF/PF) and the VC these usually resulted from the VC entering a village rather than from the RF/PF initiating offensive action against the VC. The report noted:

The operational performance of the RF does not appear to have improved over the last 12 months. In many cases the PF have proved more effective. The People’s Self-Defence Force is ineffective in a security role; only 3423 of its 26,133 members that the authorities classify as trained are armed. Because the People’s Self-Defence Force is constituted primarily from the very young and very old, its military value will always be limited.[14]

On the other hand, there were positive signs from the National Police Force. The NIC report assessed that they formed ‘a compact and cohesive force, which has steadily increased the percentage of police deployed at village and hamlet level. However, its performance, particularly in relation to the Phoenix/Phung Hoang Programme, is not impressive’.[15]

Low wages for civil servants had caused some of the more experienced public servants to seek work elsewhere. There has been perceptible improvement in the conduct of, and popular attitudes to, elections with growing numbers of candidates stepping forward to seek election. In the elections for hamlet chiefs held throughout the Province on 5 April 1970, 164 candidates stood for election in the 61 hamlets. This despite hamlet chiefs sometimes being the targets of Viet Cong assassination attempts.

Viet Cong Infrastructure

The presence of Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI) within the villages remained a stubborn problem. Vietnamese estimates put VCI strength in Phuoc Tuy at 1890 of whom 800 had been identified; the 1ATF estimate was lower at approximately 1500 and 1000 respectively. Although Vietnamese staff of the Phoenix/Phung Hoang program had been in position for nearly a year, this program had hardly affected the VCI. The report felt that the problem stemmed mainly from the intelligence community. It was fragmented and uncoordinated, each agency working in relative isolation. Numerous agencies ran agents with little coordination, cross-checks of their product or follow-up to ascertain reliability, and little direction of their efforts towards specific targets as required by the operations branch. Phoenix/Phung Hoang organization had as its sole mission anti-VCI operations, but had conducted not one operation in Phuoc Tuy in May and only two or three in the previous six months.

Other problems reducing the effectiveness of anti-VCI operations included the fear of reprisals extending up to district chief or higher, and the local origin of most VC in the Province. Relatives often served in both VC and Government of Vietnam forces, and families maintained contacts with relatives in the VC and were obliged to support and assist them. The local cadres who collected taxation and food supplies were obviously known to the villagers; VCI who distribute propaganda, rally the people to attend political discussions and lectures, and purchase excessive amounts of food, medicines and equipment, did so quite publicly. There was however, a distinct reluctance to give information that could result in family losses.

Most VCI eliminations in Phuoc Tuy Province were a direct result of Task Force operations. For example, in May 1970, 18 VCI were eliminated but none by the Province Phoenix/Phung Hoang organisation. Few of those eliminated had been important cadres at village level, most being low-level supply organizers. Nevertheless, the District Secretary of Chau Duc and the Secretary of the Village Party, Binh Ba, both killed by 1ATF, were important. These losses were reflected in lowered efforts in propaganda, tax collection, and political motivation of the people, and a lack of coordination between VCI and VC units.

Chieu Hoi (or ralliers)

The report stated that the number of enemy deserters in Phuoc Tuy Province had never been high. It stated that the newly formed 1ATF Psychological Warfare Platoon had significantly increased 1ATF’s capacity to conduct psychological operations in support of the Chieu Hoi program. Data collected from interrogation of ralliers in March 1970 showed that 80 percent had seen leaflets promoting the Chieu Hoi program and 86 percent had heard air broadcasts showing that these methods of ‘contacting’ the enemy were successful. Of those ralliers interviewed, 86 percent believed the air broadcasts were more effective than the leaflet drops.[16] But problems remained. Technical problems with broadcast equipment had taken prevented air broadcasts and support from the local civil authorities was patchy. The report noted

The Province Chief has not given his full support to Psychological Operations programmes, and as a result of his failure to become closely involved there is a lack of drive and targets are not being met. The Province Chief is making less effort than had been expected in holding political meetings and explaining the GVN’s policies to the people.[17]

Province economy

The report noted that good road networks, high prices and improving security had led to a resurgence in economic activity.[18] But a perennial issue, the transfer of land from landlords to the peasants, known as the ‘Land to the Tiller’ program, was still floundering. Though the National Assembly had passed the necessary laws to implement the program, and the program was being widely publicized, a program of re-distribution of the land within Phuoc Tuy Province was not yet functioning. The report noted that there was mounting evidence of popular concern at the delays in implementing the program.

Conclusion

The NIC reports, appearing monthly from May 1970 through to the withdrawal of Australian forces in late 1971 provide a comprehensive review of the changing situation in Vietnam from an Australian perspective. They also provide a deeper analysis of the situation in Phuoc Tuy Province, complementing the Australian Embassy/HQ AFV Monthly Pacification Report. As the May NIC report described above shows, the Australian view of the campaign was often sceptical of many of the claims made in U.S. assessments.

The monthly Phuoc Tuy Pacification Committee initiated by Ambassador Harry and Major General Hay, Commander, Australian Force Vietnam, produced regular reports on the political, economic, social and military situation in Phuoc Tuy from June 1969. These reports supplemented the NIC reports which began in June 1970 and included a month by month assessment of the campaign throughout South Vietnam. It seems surprising, given the scale of Australian involvement in the campaign, that a regular system of reporting had not been implemented much earlier. Clearly, Minister Fraser was sceptical of some claims in U.S. and GVN reporting on the campaign and was seeking an independent Australian view. The monthly Phuoc Tuy Pacification report and the NIC reports provided a more realistic assessment of the situation. They now form an important month by month view of the campaign through Australian eyes.

Malcolm Fraser continued to serve as Minister for Defence until March 1971 when he resigned following a dispute with then Prime Minister John Gorton.

Notes:

[1] Peter Edwards (ed.), Sir Arthur Tange, Defence Policy-Making: A Close-up View, 1950-1980 – A Personal Memoir, Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, ANU Press, 2008, p. 32.

[2] National Archives of Australia, A1838, item 668/6/2 Part 1, National Intelligence Committee [NIC] notes – Monthly Report on Vietnam. Letter, R.L. Harry, Ambassador, to the Secretary, Department of External Affairs, 7 April 1970.

[3] National Archives of Australia, A1838, item 668/6/2 Part 1, National Intelligence Committee [NIC] notes – Monthly Report on Vietnam. Letter, R.L. Harry, Ambassador, to the Secretary, Department of External Affairs, 7 April 1970.

[4] National Archives of Australia, A1838, item 668/6/2 Part 1, National Intelligence Committee [NIC] notes – Monthly Report on Vietnam. Letter, D.J. Horne, for Secretary Department of External Affairs, to Australian Embassy Saigon, 9 June 1970.

[5] National Archives of Australia, A1838, item 252/3/5/A, Monthly Reports on Vietnam. National Intelligence Committee, Department of Defence, Canberra, Monthly Report on Vietnam: May 1970. (NIC note no. 2/70, Thursday 2nd July 1970).

[6] Ibid.

[7] National Archives of Australia, A1838, item 252/3/5/A, Monthly Reports on Vietnam. National Intelligence Committee, Department of Defence, Canberra, Monthly Report on Vietnam: May 1970. (NIC note no. 2/70, Thursday 2nd July 1970).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid. The People’s Self Defence Force (PSDF) was a volunteer force created by the GVN following the Tet Offensive of 1968 in response to popular demand. It generally consisted of those ineligible for conscription into ARVN due to their age, being too young or too old. They were intended to perform basic security tasks such as manning defensive bunkers and watch towers. One of the main reasons for the formation of the PSDF was to encourage villagers to make a commitment to support the GVN.

[15] Ibid. The Phoenix/Phung Hoang program aimed to eliminate the VCI.

[16] Ibid. Also see the article by Derrill de Heer, Australian Psyops in Vietnam 1970, on this site.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid. Also see the article by Robert Hall, Social and economic development: Phuoc Tuy 1966 to 1971, on this site.