By Bob Hall

The Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), especially their Regional Force and Popular Force (RF/PF) components, had a reputation for poor combat performance. Brigadier S.P. Weir, Commander 1ATF from 1 September 1969 to 31 May 1970, expressed the concerns of many 1ATF soldiers when he remarked that

Some of these [ARVN Regional Force] companies were so idle, so corrupt, so poor. There were cases where they tried to kill our advisers – where they were infiltrated by VC – [where] our fellows were ambushed … it was terrifying … in some cases – not in all cases, but in sufficient to make it a worry.[1]

It’s true that corruption, poor leadership, low morale, high desertion rates and other factors affected their combat performance. Some of these factors were the result of the flow-on effects of rapid expansion combined with the parsimonious allocation of funding and equipment.

But some commentators have shown that throughout the Republic of Vietnam, ARVN, and the RF/PF in particular, were carrying more than their fair share of the fight. For example, Andrew Krepinevich has argued that

Except in 1968, it was more dangerous to serve in the RF and PF units than in the ARVN. Furthermore, as time went on, the disparity in casualty rates between the forces actually grew wider. Thus, the paramilitary forces, manned by the dregs of the manpower pool and shabbily equipped compared to their counterparts in ARVN, bore the brunt of the war.[2]

Casualty rates though, in themselves, are not a good measure of combat effectiveness. High casualty rates may be due to poor tactical performance. A clearer view of the combat performance of ARVN, and the RF/PF in particular, and the factors that may have contributed to it, is indicated by the fact that in 1971, the RF/PF accounted for 51 per cent of Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces strength, but received a modest 20 per cent of the military budget. Despite this underfunding, they caused nearly 40 per cent of enemy KIAs throughout the country, showing that, together with their casualty rate, they were making a substantial contribution to the war.[3]

In this article we provide some information that may help to explain, to some extent, the sometimes poor combat performance of the ARVN and help to provide a more balanced and realistic assessment of their capabilities.

ARVN combat capability compared to Free World Forces

In December 1968, Colonel A.F. Swinbourne, the Military and Naval Attache at the Australian Embassy, Saigon, wrote a report on the development and capability of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF).[4] Swinbourne’s report noted that at that time, the RVNAF consisted of 10 Infantry Divisions and two independent regiments, plus other combat support and logistic troops. Three of the infantry divisions were located within III Corps Tactical Zone which was commanded, at that time, by Lieutenant-General Do Cao Tri. They were 5, 18 and 25 ARVN Divisions.

Swinbourne emphasized that ARVN Divisions were not as powerful as US Army or Australian Divisions. While a US Division numbered 16,626 men, an ARVN Division mustered only about 12,000. Each US Army infantry battalion had a strength of about 970 men whereas ARVN infantry battalions were only two-thirds that size with about 650 men. Furthermore, ARVN infantry battalions had fewer vehicles, mortars and automatic weapons than their US or Australian equivalents.

ARVN soldiers train with Australian troops at the Horseshoe, Phuoc Tuy province

Whereas the Australian and US Army concept was to group nine battalions in the Division into task forces designed to meet specific operational requirements, ARVN Divisions had a basic organization of three regiments each of four battalions giving a total of 12 battalions per division. The 1st Australian Task Force, based at Nui Dat between May 1966 and October 1971 initially had two, later three infantry battalions, some of which were reinforced with extra New Zealand rifle companies plus additional mortars, and other support elements. 1ATF units could call on the support of an 18-gun Regiment of 105mm artillery, plus additional medium and heavy artillery supplied by the US Army. However, ARVN Divisions of 12 infantry battalions were supported by just two artillery battalions, each equivalent to an Australian Artillery Regiment. ARVN infantry therefore had about half the artillery support of an Australian infantry battalion.

With fewer men, less integral firepower and about half the artillery support of an Australian battalion, it is little wonder that ARVN infantry battalions seemed to underperform relative to their Australian or US Army equivalents. Few Australian infantry battalion Commanding Officers, let alone their subordinate commanders and soldiers, would have been happy to engage VC or PAVN forces like D445 or 33 PAVN Regiment, with the level of support available to ARVN battalions. Yet this was common fare for ARVN infantry units.

The men of 1ATF were often critical of the ARVN troops they saw in Phuoc Tuy Province but 1ATF troops tended to see the worst performing ARVN field units. Within III Corps Tactical Zone (III CTZ), the areas of highest strategic priority were those provinces between Saigon and the Cambodian border. The greatest threat to the survival of the Republic of Vietnam came from the VC/PAVN forces in that area. The Vietnamese high command allocated their best formations, 5 and 25 Divisions, to that area. On the other hand,18 ARVN Division was widely regarded as one of the poorest performing Divisions in the South Vietnamese Army. It was allocated to the area of lower strategic priority within III CTZ; the provinces east of Saigon, where its units came in contact with 1ATF. Nevertheless, despite its poor reputation it should be remembered that 18 ARVN Division performed outstandingly in the defence of Xuan Loc against overwhelming PAVN forces in the days before the fall of Saigon in 1975.

The Regional Force and Popular Force

The Regional Force and Popular Force (RF/PF) troops had a particularly poor reputation for combat effectiveness. But once again, deficiencies in organization and armaments go a long way to explaining their combat shortcomings.

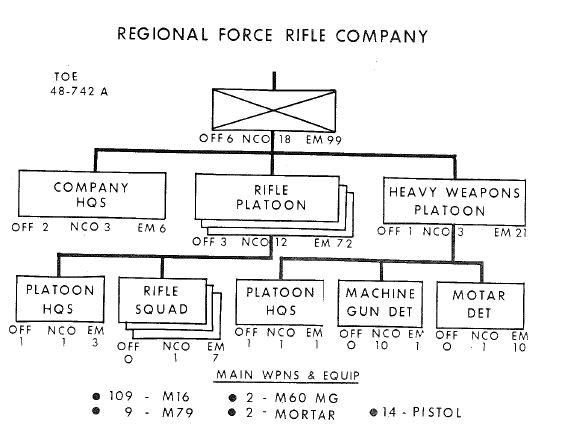

Although organized along rifle company lines, RF companies had only two 7.62mm M60 machineguns.[5] RF companies had responsibility for patrolling and dominating the ground on the approaches to the villages. They were required to conduct patrol and ambush operations into the jungle in an attempt to bring the VC/PAVN to battle. But if they were to patrol beyond their bases, they were faced with the problem of whether to take their two machineguns on patrol with them, or leave them to defend their base (that usually housed their families), while the majority of the company was absent on patrol. Neither option was good. As a result they often lacked the dominating firepower of a machinegun to allow their infantry to successfully manoeuvre while in contact with the enemy. Unsurprisingly, to many observers they seemed to perform poorly against the much better armed VC/PAVN.

Regional Force company organisation. Note that the table of weapons and equipment shows only 2 M60 machineguns and 2 mortars per company

In contrast, an Australian rifle company had ten 7.62mm M60 machineguns and when platoons operated as two half-platoon patrols as they often did from mid-1969 through to the withdrawal of 1ATF from operations, they were usually equipped with extra M60s bringing the company total to 13 machineguns. While 1ATF rifle company patrols were out beyond the Nui Dat perimeter wire, the base remained secure behind its perimeter bunkers each equipped with an M60 or sometimes, a .50 calibre machinegun. 1ATF companies never faced the problem of having to leave their machineguns back at the Nui Dat base for perimeter defence. Furthermore, if an unexpected threat to the Nui Dat perimeter arose at short notice, the Nui Dat base had a counter penetration force available and APC and helicopter troop lift could quickly reinforce the base by bringing forces deployed on operations back to Nui Dat if necessary. These options enabled 1ATF patrols to take substantial firepower on operations while still maintaining the security of their Nui Dat base, a luxury the RF never enjoyed.

RF companies did not compare with equivalent sized VC or PAVN units in terms of infantry weapon firepower. At the time of Swinbourne’s report, VC provincial force squads were typically armed with three SKS carbines, four AK47s, an RPD LMG and an RPG2 or RPG7. People’s Army of Viet Nam (PAVN, also known as North Vietnamese Army or NVA) infantry squads were usually armed with three SKS carbines, six AK47s and an RPD LMG.[6] Heavy weapons support such as mortars, RPGs, HMGs and recoilless rifles, were available within the battalion heavy weapons company.

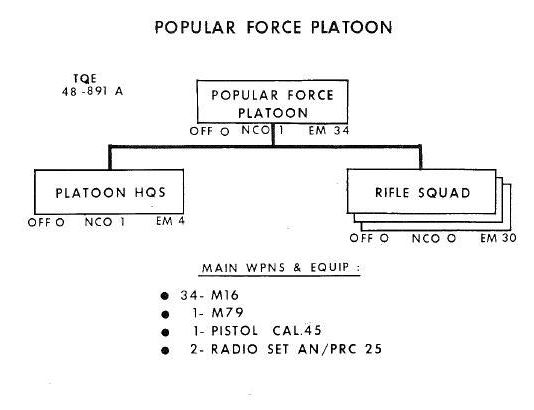

Popular Force platoon organisation. Note that the Popular Force platoon has only 1 NCO providing leadership and no machineguns. Facing the VC/PAVN with such an underarmed force was sure to lead to poor combat performance.

Whereas the RF was organised along company lines, the ARVN Popular Force (PF) was organized as a series of independent platoons.[7] Remarkably, these platoons consisted of three squads of 10 soldiers each, with the whole platoon commanded by a single NCO. A 1ATF platoon was of similar strength but was commanded by an officer with a Sergeant, three Corporals and three Lance Corporals through which to exercise his command. It is little wonder that PF platoons lacked leadership. Furthermore, if the NCO in charge of a PF platoon became a casualty, his platoon was left rudderless. In contrast, 1ATF and other Free World Forces platoons had a hierarchy of command and if the platoon commander became a casualty, the next man in the hierarchy immediately took his place and leadership continued to function.

To make matters worse, the PF platoon had no machineguns. Its ability to produce fire in contact depended upon the platoon’s M16 rifles and a single M-79 grenade launcher. It was frequently outgunned by its VC/PAVN opponents.

Regional Force soldiers prepare to deploy on an operation by RAAF helicopter. Note the soldier on the right with his hand to his helmet is wearing thongs on his feet.

The Popular Self Defence Force

The Popular Self Defence Force (PSDF) is sometimes wrongly thought to be part of ARVN. In fact it was a civilian, part-time, volunteer organisation for local static protection of populated areas. Swinbourne reported that there was a total of about 421,700 PSDF personnel throughout the whole of the Republic of Vietnam (in December 1968) with a further 134,000 under training. Of the total PSDF strength, a fraction – only about 39,000 – were armed. Their weapons were obsolescent small arms of World War II vintage – mainly Garand semi-automatic rifles, M1 carbines and Thompson sub-machineguns.

Swinbourne reported that US officers at HQ MACV did not think that the PSDF provided a significant defence element. Instead, the PSDF played a psychological role. Although South Vietnamese authorities felt that it was dangerous to arm the population too extensively lest the weapons fall into the hands of the VC/PAVN, the main effect of the PSDF was to ‘induce a feeling of togetherness and cohesion in sections of the population, and thus prevent accommodation of infiltration by enemy forces and infrastructure’.[8] Swinbourne noted this effect in Can Tho where, prior to the formation of the PSDF, individuals had been too afraid to organize against VC penetrations of their villages. With the PSDF structure in place to support them, the people had set up a network of gongs to warn of enemy activity.

The PSDF should not be thought of as a part of the Republic of Vietnam’s armed security apparatus. Instead, it was an agency through which citizens were encouraged to commit to the support of the government. It was never considered part of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces and its very limited combat capabilities should form no part of a general assessment of ARVN.

Many factors contributed to the patchy performance of ARVN units and particularly to the combat performance of RF/PF. While some regular ARVN units performed to a very high standard, others were less capable. Regional Force and Popular Force units were often thought to be of the most marginal quality. Although a wide range of factors may have contributed to this outcome, the limitations of organization and equipment described above account for a considerable part of this under performance.

Notes

[1] Brigadier Weir quoted by Frank Frost. See Frost, Australia’s War in Vietnam, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1987, p. 141.

[2] Krepinevich, The Army and Vietnam, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1986, p. 220.

[3] Lewy, America in Vietnam, Oxford University Press, New York, 1978, p. 182.

[4] AWM121, item 4/B/31, Operations – SVN – ARVN/RF/PF – General. Memo, Colonel A.F. Swinbourne, Military and Naval Attache, Australian Embassy Saigon, ‘Development and Capability of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF)’, dated 31 December 1968.

[5] Advisors Handbook, RF/PF, Appendix I-11, HQ USMACV, 1 January 1971.

[6] ‘NVA/VC Small Unit Tactics and Techniques’ dated 22 March 1969.

[7] Advisors Handbook, RF/PF, Appendix I-12, HQ USMACV, 1 January 1971.

[8] AWM121, item 4/B/31, Operations – SVN – ARVN/RF/PF – General. Memo, Colonel A.F. Swinbourne, Military and Naval Attache, Australian Embassy Saigon, ‘Development and Capability of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF)’, dated 31 December 1968.

One Comment on “The ARVN: Was their performance misunderstood?”

Pingback: Vietnamese & Australian joint operations 1961-2 | RAAF Documentaries