Courtesy and copyright of E S Holt. Photos courtesy of Norm Gomm.

- Demonstrating the XM 203 M16 fitted with an underslung 40mm grenade launcher

- The 6-lb boat fully inflated

- This 6-lb inflatable boat was used by the SAS

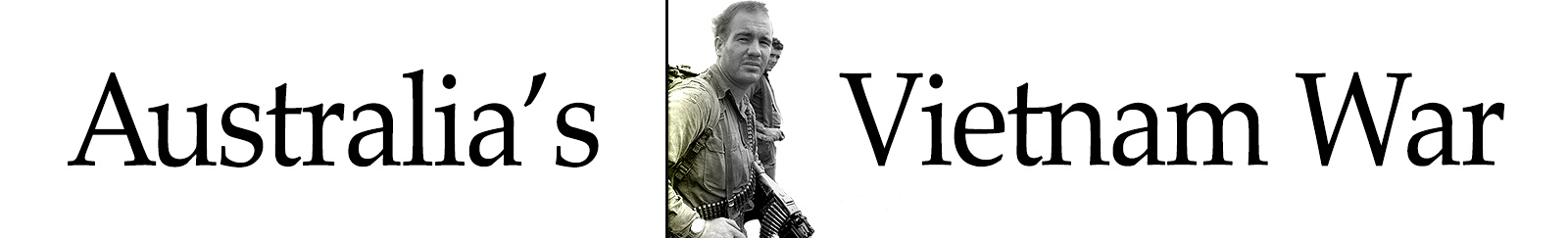

- The ADE XH-6 Delay Firing Device

- From the left, Captain Pearson (ARPA), Major Barnard (ARPA), Captain Norm Gomm (FORS), Major Smith (FORS). The team were about to depart by Air America, the CIA’s private airline, to visit a US Special Forces activity

- Captain Norm Gomm of FORS at Nui Dat

- This experimental firing device was later adopted for service. It could be used to control the fire of multiple banks of claymore mines or other explosive devices

- The FORS tent lines at Nui Dat

- The log periodic antenna ‘borrowed’ from 7th US Air Force and installed on SAS hill at Nui Dat to establish long-range communications with deployed SAS patrols. The SAS liked it so much they took it with them when the Task Force withdrew from Nui Dat

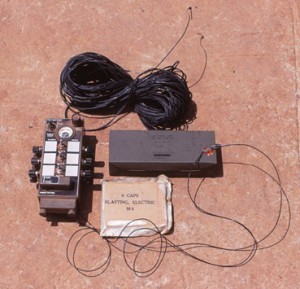

- Mini-gun converted for ground use at a CIDG Fire Support Base

- Dispersed operations called for radio communications down to section level. FORS trialled the use of a range of squad radios like those above

- Helium filled balloons like this lifted VHF radios above SAS hill at Nui Dat so that line of sight communications could be established with SAS patrols deployed to the fringes of the Province

- XM 174 (2) a multi-shot 40mm grenade launcher

- XM 191 ready to fire

- The XM 191 was similar to a 4-shot M72 but fired a rocket propelled warhead filled with a napalm-like substance

Operational Research arose out of the Battle of Britain, in WWII. It had been foreshadowed by F. W. Lanchester in Aircraft in warfare: the dawn of the fourth arm, written in 1916. Described as ‘a scientific method of providing executive departments with a quantitative basis for decisions regarding operations under their control’, and instigated by Professor P. M. S. Blackett, the methods of scientific research were applied on a large scale to the study of the performance of new types of equipment, and to the operations of war.

Describing a case of outstanding achievement by Operations Research, Sir Charles Goodeve, in Operations Research, 1948, wrote ‘as is well known, we had in 1940 few fighter aircraft compared with the number that would have been needed to defend (Britain’s) shores. It would have been impossible to obtain sufficient interceptions.’ With the invention of radar, which allowed the retention of fighter aircraft on the ground until needed, ‘Ground Control’ was able to direct aircraft to a position where the enemy aircraft could be sighted visually and attacked. A small party of scientists was attached to Fighter Command to study and refine the efficiency of the interception system. These scientists learned to estimate which targets were ‘good’ and which were ‘bad’, and to determine where and how the limited resources could be most effectively used. Radar is estimated to have increased the possibility of interception by a factor of about ten: and this small research team increased the probability by a factor of two, which together meant that the Air Force was made 20 times more powerful, a doubling which was out of all proportion to the amount of effort spent on the research.

During WWII, an Australian group sponsored by Major-General J. S. Whitelaw began work with the Army Operational Research Group which was under Dr D. F. Martyn’s leadership in June 1942. Martyn’s group concentrated their efforts on weapons research, more specifically on the capabilities of radar. He recruited mainly science graduates with honours degrees in physics and mathematics – not men with experience in engineering. One of these graduates was George Cawsey, who later became Scientific Advisor to the Military Board, (SAMB) in 1964.

Cawsey was a brilliant scientist and a clever organiser. In 1965 he convinced Brigadier G. D. Solomon that the Australian Army Group sent to South Vietnam must be accompanied by a Field Operational Research capability. Solomon was also a graduate not only of Staff College (UK) but also of the Royal Military College of Science (RMCS), located at Shrivenham in England. It was therefore not circumstantial that the military officers selected for Field Operational Section, Vietnam, or FORS-V, were mostly graduates from RMCS. The civilian scientists who were posted to FORS-V were principally mathematics or physics graduates, temporarily promoted to captain for the duration of their service with FORS.

FORS consisted of two officers – the Officer Commanding being a Major and the second in command being the civilian scientist – and a clerical sergeant with sufficiently high security clearances for the work FORS would be doing in Vietnam.

Due to politics and restrictions imposed on troop strength in Vietnam, this staff was never increased. There were two officers and a sergeant when the Australian forces consisted of a battalion group, and still three when the Australian Army in Vietnam had increased to three battalions, with three batteries of artillery, a squadron of Engineers, and a squadron of tanks, not to mention the 1st Australian Logistic Support Group at Vung Tau and all the supporting arms and units needed to keep the three battalion task Force operational.

Initially located with the US Army Concept Team in Vietnam (ACTIV) at Saigon, and working from HQ AFV, also in Saigon, one of the first tasks given to FORS by the US Commander was to develop a data base. ‘If you don’t have a data base, how can you begin to study the operational requirements of your Aussie forces.’ Major Ian Meibusch, the first OC of FORS-V, set about developing a data base.

A small report called After Action Contact Report was developed by FORS and sent to 1st battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. To begin, the report was acceptable back at FORS if it was written in pencil on a page torn from a field notebook. FORS began to find out just what had happened in contacts with the enemy, the Viet Cong /People’s Army of Vietnam (often referred to in Vietnam war-era documents as the North Vietnamese Army, or NVA). The questions included:

- How many rounds were fired in the contact and by whom?

- What initiated the contact?

- Who initiated the contact?

- How was it initiated?

- What casualties were sustained by both sides?

- Who fired the first shot?

- What weapons were used by both sides?

- When did the contact occur and how long did it last?

- What was the map reference?

- And always at the end, ‘What lessons were learned?’

The wording of the questionnaire was refined as more information was found out about contacts with the enemy and the data base began to build. A separate problem occurred, however, in that units began to use the ‘Contact After Action Report’ in the Battalion’s much lengthier After Action Report, which increased and increased in size as Commanding Officers began to write at length about an operation which may have lasted four to eight weeks. Platoon commanders were required to have their After Action Contact Reports typed and run through a messy ink ‘Gestetner’ machine needed to produce the number of copies required at Company and Battalion Headquarters. Task Force required multiple copies for distribution to 2 Field Force-V, HQ AFV in Saigon, and multiple copies to be sent back to Australia for senior officers to read and engage in tooth-sucking exercises.

The After Action Contact Reports which were sent on to Scientific Advisors Office were neatly recorded on ‘The Holey Man’, a larger than life-sized array of graph sheets glued together, representing the outline of a human figure. The position of the wounds received were entered on the figure, and referenced to a numbered Contact Report.

This ‘Holey Man’ was used to dissuade the then Engineer in Chief who wanted to spend the not inconsiderable amount of $25,000 in 1967 to investigate injuries caused by panji stakes, which were either fire hardened and sharpened bamboos stakes or later were metal spikes, hidden in the long grass around a Viet Cong village to injure a soldier who stumbled or fell to the ground, or who threw himself down in the grass when firing began. The ‘Holey Man’ showed that there had only been two serious panji spike injuries since the Australians went to Vietnam in 1965.

The ‘Holey Man’ also showed that 33% of injuries to Australian were caused by mine explosions – usually the same M16 mines which a Task Force Commander had ordered to be laid through paddy fields and crops from the Task Force outpost at ‘The Horseshoe’ feature to the coast, a distance of about 10 kilometres. The VC and villagers were digging up these M16 mines and using them against us. They reasoned ‘Why go to all the trouble of sharpening bamboo stakes when one well laid M16 mine could cause so much more damage?’

Many of the M16 mines had a hand-grenade attached underneath it to hopefully prevent the mine from being lifted, so the VC reasoned ‘Why not use one of the hand-grenades and a trip wire outside the village rather than sharpened bamboo stakes?’ Panji stakes almost disappeared from Viet Cong defences.

The Engineer in Chief recognised immediately that his $25,000 would be better spent on researching ways to defeat mines and hand grenades used by the VC/NVA against the Australian Forces.

As the CO of ACTIV had said to Major Ian Meibusch in 1965 ‘If you don’t have a data base, how can you begin to study the operational requirements of your Aussie forces?’

FORS was directed to solve many problems, including finding a way to defeat Falciparum malaria, a virulent form of malaria being brought down the Ho Chi Minh Trail by North Vietnamese soldiers. At one time after operations in the May Tao mountain area, the infantry had 50% casualties from malaria, a high rate which could not be sustained by the Task Force.

On being told by Army Headquarters Melbourne that the high incidence of malaria in his operational troops was simply a matter of discipline, the Commander AFV, Major General A. L. MacDonald, responded with a roar which was possibly heard in Hanoi. It was certainly heard at AHQ in Australia.

Shouting for OC FORS, MacDonald asked ‘can you design and run a trial to see if this new anti-malaria tablet can really be used to defeat malaria at Task Force?’ He added that the US Walter Reed Military Hospital had attempted to trial these Dapsone tablets in Vietnam and had failed embarrassingly. It is now history that the FORS trial was hugely successful, a fact which A. L. MacDonald largely enjoyed relating to HQ MACV, the Headquarters of the American Forces in Vietnam. Falciparum malaria casualties dropped to zero in the test group, and Dapsone was introduced, dramatically reducing malaria casualties in the Australian Forces in Vietnam.

This, of course, was not specifically a FORS task. Army should have sent a team of medical and scientific officers to Vietnam to investigate and report on the falciparum malaria problem, but politics controlled the maximum number of personnel who could be in Vietnam at any one time, and the ceiling had been reached at least two years earlier. This was another reason why FORS was not allowed to increase its staff as the size of the Australian commitment doubled and doubled again.

It is interesting to note that a second Army Operational Team sent out from UK to Australia in 1943 were given a charter which more closely matched the work that FORS-V found itself doing in Vietnam. Its charter was biased towards the study of weapons and equipment, principally in the collection of factual and scientific data on the performance and tactical handling of operational equipment – our own and the also the enemy’s.

‘The primary function of an operational research section’, wrote Lieutenant General John Northcott in 1943,

is to establish factual evidence in forward areas on both tactical and technical value of weapons and equipment. This evidence is obtained by:

- The collection and critical analysis of facts and quantitative data of military problems as opportunity offers and by critical appreciation of new or modified weapons before or after they reach the user;

- Scientific assistance in the planning and reporting of trials and experiments carried out locally and in the solution to immediate problems, such as countering new enemy weapons or techniques;

- Collection and critical analysis of eyewitness reports and opinions from both our own troops and prisoners of war.

The role of FORS-V could not have been set out any more accurately than this. However, to believe that two officers, one a civilian scientist in uniform and the other a graduate of RMCS, could manage to competently cover all aspects of the task in South Vietnam, was patently ludicrous.

The equally-ludicrous requirement set by AHQ Canberra – for FORS to also study the problems of organization and logistics of the US Army in South Vietnam – was ignored, as the small staff soon became deeply involved in detailing the need for improved weapons and equipment for the Australian Forces in Vietnam, and the introduction of new or experimental weapons and equipment by the US Army.

Below are just three examples of major projects undertaken by FORS-V during one twelve month period, to which can be added the successful Dapsone counter-malaria trial:

The SAS Squadron needed reliable communications at all times for their patrols operating in and behind enemy lines. Thinking laterally, FORS-V officer Captain Tom Millane, ‘borrowed’ a huge log-periodic antenna from 7th US Air Force, and Detachment 152 Signals Squadron erected it on SAS Hill at the Task Force Base at Nui Dat. This antenna was arranged so that it sent high frequency transmissions vertically upwards, where the signal could be reflected from the ionosphere and received by an SAS patrol which did not have line-of-sight back to SAS Hill. SAS liked the LPH-17 antenna so much they ‘forgot’ to return it to 7th US Air Force, and took it with them when the Task Force Base at Nui Dat was vacated.

Captain Millane also arranged to ‘borrow’ several barrage balloons from 7th US Air Force, which, when filled with 170 cubic metres of helium, carried a VHF radio and cables high above SAS Hill to provide line-of-sight VHF communications to SAS patrols. ‘It was like having the Ops Officer standing alongside me providing info direct to the patrol’ said one extremely grateful SAS signalman.

OC FORS, Major ‘Tim’ Holt, put a plan to the COMAFV for a roller, made from water pipe and old truck tyres, to be towed offset to one side of an M16 armoured personnel carrier, to render the notorious Task Force ‘Barrier Minefield’ safe. It was a paper study which drew information from US Army Field Handbooks, a chance photograph in the American ‘Stars & Stripes’ newspaper, and the lateral thinking with which Australians seem to be abundantly blessed. 1 Field Squadron’s Light Aid Detachment cobbled the roller together, and although – to quote one APC driver ‘It was a (expletive deleted) pig to steer’ it did the job and, and for the first time since it had been laid, the Task Force minefield ceased to be a source of M16 mines and hand-grenades to the enemy.

The Royal Australian Air Force did not have an Operational Research capability during the Vietnam War, although it had been keen to use OR during the latter stages of WWII. Defence keenly employed several operational research teams during the recent Afghan War, with an increasing awareness of the value of operational research in all its facets.

Editor’s note: For those interested in further research on FORS and its activities in Vietnam, and the application of science to combat operations, there are a large number of FORS files held in the collection of the Australian War Memorial. The following examples show the range of subjects dealt with by the small FORS team:

- AWM98, R237/1/22/1 PART 2, [Headquarters, Australian Force Vietnam (HQ AFV):] Correspondence – General – FORS [Field Operations Research Section] – SAO [Senior Administrative Officer] – [Includes material on casualty reports, soil samples, sound ranging system at Nui Dat, report on the use of dogs to detect tunnels, mines and booby-traps, lists of research projects and British lessons learned from Vietnam War 1969 – 1969.

- AWM98, R237/1/22/3 PART 4, [Headquarters, Australian Force Vietnam (HQ AFV):] Correspondence – General – FORS [Field Operations Research Section] – SAO [Senior Administrative Officer] – [Includes material on night sights and infrared devices, activities of FORS in Vietnam, water tanks and personnel detection radars] 1970 – 1970.

- AWM279, 2/6, [FORS [Field Operations Research Section] 9] Evaluation Small Arms/Munitions Detector in RVN [Republic of Vietnam] circa1969 – circa1969.

- AWM98, R310/2/11 PART 1, [Headquarters, Australian Force Vietnam (HQ AFV):] [Establishments] – Field Operational Research Section (FORS) Attachment, South Vietnam [File contains documents relating to the posting, strength, accreditation, and tasks of FORS in Vietnam, including description of tasks from Dec 1965, reports on R&D items of equipment, an extensive report from the Scientific Advisor to US MACV on Data Sources in South Vietnam; a ‘sanitised’ report from a Dept of Supply secondment during 1970 and 1971 dealing with FORS activities, reports on various visits and projected schedule for a AFV withdrawal in 1971-72.] 1965 – 1971.

The Australian War Memorial collection also contains a large selection of files relating to trials of experimental equipment. Some examples are:

- AWM98, item R8465/1/6, Individual Equipment Containers – Water Collapsible.

- AWM98, item R895/1/1, Water-s, General – Water Jellying Compound.

- AWM103, item R990/500/2, RAASC Supplies, Tests and Trials, Aust 1 Man Ration.

- AWM98, item R980/500/53, HQ AFV, Stores and Equipment, Tests and Trials, M67 and L14A1 Carl Gustav.

- AWM103, item R980/500/131, HQ 1ATF, Stores and Equipment, Tests and Trials – Night Scope – Rifle Sight.

- AWM103, item R980/500/128, HQ 1ATF, Stores and Equipment – Tests and Trials – Single Point Small Arms Weapon Sight.

- AWM103, item R980/500/24, HQ 1ATF Stores and Equipment – Tests and Trials – Hitachi Portable Transceiver (Squad radios).