Bob Hall, Andrew Ross and Derrill de Heer

When a 1ATF infantry patrol had a contact with the enemy, and small arms fire was exchanged, the patrol commander reported ‘Contact! Wait, out’ over the company radio network. These few words triggered battle procedures that went on well away from the patrol in contact. Those soldiers at the scene of the contact were totally absorbed in fighting their battle. They were often unaware of the battle procedure that their radio call had triggered elsewhere in the company and in the battalion command post, at the Fire Support Base and back at Nui Dat. In this article, we describe some of the battle procedure that was initiated when ‘Contact! Wait, out’ crackled over the radio network.

The response at company level

At the company level, the company HQ signallers immediately informed Battalion HQ that one of the company patrols was in contact. Other company platoon or half-platoon patrols were usually only several hundred metres from the patrol in contact and could hear the gunfire (and sometimes received the overshoots). They usually stopped patrolling, ceased transmissions on the company radio net to allow the patrol in contact to use it, and monitored the radio chatter between the patrol in contact and company HQ so that they were aware of how the situation was developing.

The patrol commanders of patrols not in contact would usually study their maps and begin planning how they might move to support the patrol in contact if the contact turned ugly. They could also study their maps for possible withdrawal routes the enemy might use as he broke contact and escaped into the jungle. There may be a nearby track, ridgeline or other feature that the enemy might use as a withdrawal route that might be worth ambushing. They would also establish the location of their patrol and encode a location statement (LOCSTAT) ready for radio transmission to company HQ. If the patrol in contact needed artillery or air support, the Forward Air Controller and the Artillery Forward Observer at company HQ, would want to know where neighbouring patrols were located so that a friendly fire incident could be avoided. When time permitted, patrol commanders would brief their section commanders on the situation.

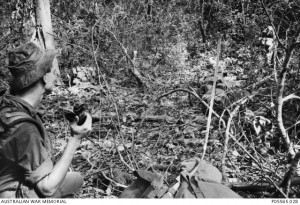

At his Company HQ command post, signaller Corporal Felix Byrne of B Company, 4RAR/NZ, takes down details radioed in by a patrol in contact.

Meanwhile, at company HQ, information about the contact would continue to be passed to the battalion command post over the battalion command radio network. The company commander would carefully monitor the developing contact and could decide to support the patrol in contact by redeploying his other patrols, or could use his other patrols to establish blocks or to ambush withdrawal routes the enemy might use. The artillery Forward Observer would pass information about the contact to the Fire Support Coordination Centre located in the battalion command post.

If the contact was with a significant enemy force and continued for more than a few minutes, the company commander might request artillery, mortar or helicopter gunship support. Some companies and battalions favoured the automatic application of indirect firepower whenever a patrol was in contact with the enemy, regardless of the size of the enemy force. But this could create problems. First, most platoon or half-platoon infantry patrols did not have an artillery Forward Observer or Mortar Fire Controller with them, so the job of adjusting the fire mission fell to the patrol commander who already had his hands full with fighting the infantry battle. Second, most contacts in the jungle occurred at very short range, usually about 20 metres or less. To apply artillery or mortar fire onto an enemy that close risked causing casualties to the friendly patrol. The 1ATF patrol would have to disengage and withdraw a safe distance while the artillery fire was applied. The enemy often seized this opportunity to break contact as well, so the indirect fire support often fell on an empty battlefield or could be used only in depth, behind the enemy.

One of the rules of applying artillery fire spelt out in 1ATF Standing Operating Procedures, was that for safety reasons, the first round of an artillery mission was to impact no closer than 1000 metres from any friendly positions. It was then to be adjusted onto the target. However, it is possible, perhaps even likely, that having studied 1ATF practice, the enemy was aware of this safety precaution. If so, the impact of the first round may have indicated to the enemy that if they withdrew towards it they could be sure that they would not contact another friendly patrol.

For these reasons, other company commanders (and battalions) favoured staying in contact with the enemy. For them, if indirect fire support was used at all, it would be applied in depth behind the enemy in an attempt to prevent his withdrawal, cause casualties to him while he withdrew, or channel his withdrawal in a particular direction, perhaps towards waiting ambushes. Patrol and company commanders often thought it was better to fight the battle with infantry weapons rather than allow the enemy to withdraw. Patrols had often spent weeks of difficult and tiring patrolling to find the enemy. Having found him, it made little sense to then break contact to apply indirect fire support, allowing the enemy to escape into the jungle again.

The response at the battalion command post

The 4RAR/NZ battalion command post was organised along similar lines to other battalion command posts. Once the message ‘Contact! Wait out’ was received, the command post sprang into action, initiating a series of battle procedures designed to support the patrol in contact.

Photo courtesy of Derrill de Heer.

Back at the battalion command post, once the signal ‘Contact! Wait out’ had been received, Task Force HQ would be alerted to the contact. If the radio communications were up to the task, the battalion command post might flick a radio onto the company command net frequency to monitor events at the contact site. Meanwhile, the Fire Support Control Centre within the command post, would alert the direct support artillery battery and, if they weren’t engaged in another mission, the guns would be swung onto target in readiness for a possible fire mission. Ground and air clearances to fire would be sought. The Dustoff helicopter on the pad at Nui Dat would be put on standby for a possible mission. Battalion quartermaster staff might move a replacement first line ammunition resupply down to the battalion LZ ready for delivery, if needed, to the patrol in contact and a helicopter gunship Light Fire Team might be put on standby awaiting the call to support the patrol in contact. Finally, the Commanding Officer might use his direct support helicopter (a Sioux or later, Kiowa) to orbit the contact site, providing whatever support he could offer the patrol on the ground.

All of this battle procedure happened within the first few minutes of company and battalion HQ receiving the radio message ‘Contact! Wait out’. Its aim was to compress, as much as possible, the reaction time if support was needed by the patrol in contact. If the contact resulted in the enemy withdrawing after a few minutes, as most did, then, once the situation had stabilized at the point of contact, the various supporting elements would be told to stand down and normal routine would resume.