By Ernie Chamberlain

“The northerners – who have had considerable infusion of Chinese blood, are noted for their aggressiveness, energy and sense of superiority toward the southerners whom they regard as indolent and inefficient. In the South, the climate is more tropical, there is more rich soil and less population congestion.” See footnote 37.

“The VC enjoy eating some vegetables raw while the NVA troops wanted them boiled.” See footnote 41.

“… dietary differences eg; Southerners did not eat dog meat – a Northern taste”. See footnote 20.

“USMACV closely followed reports of NVA versus VC dissension and friction. At a weekly intelligence conference on 20 September 1969, General C.W. Abrams (COMUSMACV) remarked: ‘Christ, you can’t get them ((NVA and VC)) together at a free beer party, really.’ See footnote 43.

“In Phuoc Tuy especially – regroupees and northerners had assumed most of the principal command positions ((in communist forces)).” See footnote 49.

“… female SVN cadres and the Vietnamese residents in Cambodia usually like to make friends with NVN-born cadres and soldiers. Due to this reason, SVN-born cadres and soldiers search for means to calumniate ((ie to make false or defamatory statements)) against their opponents.” See Annex B, p.24.

An Overview

During the Vietnam War, the US and the Republic of Vietnam (ie South Vietnam) actively highlighted the presence of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops fighting in the South. However, despite being aware of tensions and divisions between the Việt Cộng and the NVA in late 1965 – evidenced in intelligence reporting including captured communist reports and directives, the US and Saigon were “initially more cautious and circumspect in exploiting any divisiveness among the communists in South Vietnam.” (footnote 34).

However, six months later, US “guidance” was more aggressive – in its assessments of “Contradictions and Cleavages – Northerner Versus Southerner.” (footnote 35). However, throughout most of the War, the US and Saigon were wary and reticent to actively exploit divisions between the VC and the NVA in the South – noting: “A national campaign seeking to play on sectional prejudices is not in our long-range interests and would run counter to the present National Reconciliation Program of the Government of Vietnam.” (footnote 27).

From 1969, the US and Saigon Government did, at times, seek to exploit differences and tensions between Northern and Southern communists. (footnotes 36-38).

Southern-born “Regroupees” in the North returning to the South – and Tensions

During the Vietnam War, tensions in South Vietnam among “Southern-born” Việt Cộng soldiers and cadre had their origins in the “regrouping” (tập kết) in the mid-1950s of several thousands of Việt Minh from the South to North Vietnam (ie the Democratic Republic of Vietnam) following the Geneva Accords of July 1954.[1] Termed “regroupees” (cán bộ hồi kết), most US reporting numbers these Việt Minh “regroupees” from the South as 80-90,000.[2] However – according to a “Sensitive Top Secret” US report (dated circa late 1967), in 1954-55 there were 130,000 “Viet Minh departures ((from the South)) for the North (comprising 87,000 Warriors, 43,000 Admin cadre, liberated POWs, and families)” – of whom 16,000 “admin” had assembled at Hàm Tân/Xuyên Mộc.[3]

Both the on-site VC commander at the Battle of Long Tân in August 1966 – Trần Minh Tâm (the deputy commander of the 5th VC Division) and Nguyễn Thới Bưng (commander of the 275th Regiment) had earlier regrouped to the North, trained, and infiltrated back into the South.

Farewelling “regrouping” Việt Minh departing the South for the North – 1954

“Originally the training of ‘regrouped’ VC for infiltration back into the Republic of Vietnam was conducted at four different locations in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The 324th Division ran a school in Nghệ-An Province, the 305th Division ran a school in Phú-Thọ Province, and the 83rd Division ran schools in Hà Nội and at Xuân-Mai ((in Hà Đông Province)). The system was changed in 1961 ((Note: The exact date is not given)). At that time the 338th Brigade was placed in charge of the entire program, under the control of the Ministry of National Defense centered at Xuân-Mai.”[4] The first “infiltration group” from the North – of 400 men, “departed Xuân-Mai on 20 February 1960 to … Quang Ngai Province (South Vietnam) and became the 70th Battalion.”[5]

Those Southerners who had regrouped (“regrouped” = “hoàn kết”) to the North were colloquially termed “Autumn cadre” (cán bộ mùa thu) – while those who had remained in the South were termed “Winter cadre” (cán bộ mùa đông). A VC civilian provincial official responsible for intra-unit cadre relations stated: “The Winter cadres ((Southerners who remained)) often despise the Autumn [regroupee] cadres because they [the Winter/Southern cadre] have fought for over ten years in the South in hardships and now the Autumn ((“regroupee”)) cadres – who had lived in peace for a long time in the North, come to be their leaders. The Autumn ((“regroupee”)) cadres are confident in the education, training and knowledge they’d obtained – so they encroached upon the Winter cadres …. .” An assistant platoon leader found the situation in his main force unit in IV Corps (Mekong Delta region) much more serious. He described the regroupee versus local Southerner conflict over promotions as a “struggle for position.”[6]

In an interview by US analysts, a VC rallier – born in the South but who had not been to the North, related that: “There was discrimination between ‘autumn combatants’ ((regroupees)) and ‘winter combatants.” The autumn combatants ((Southerners who had been trained in the North)) were more favored …. They are called so ((ie “Autumn cadre”)) in view of the time of the year when they joined the army. Autumn combatants are regrouped soldiers, who had lived and had been trained in the North. There were differences in treatment with respect to rank, promotions, and living conditions. The autumn combatants behaved loftily, being proud of having been to the North. Soldiers of the two seasons were in casual brawls but did not fight one another.” Another Southern-born VC defector noted: “Many of these autumn cadres had gone to the North unmarried. They stayed unmarried in the North for 9 or 10 years – and now they had returned to the South. Most of them were 40 or more. They wanted to get married. … women were very proud to have them for husbands. They were proud to have husbands who were officers. We new recruits, we didn’t want to get married — and they weren’t interested in us. … The Southern cadres and fighters endured hardships for years, while they ((regroupees)) were enjoying themselves in the North where peace prevailed. And now, when the struggle had already started in the South, they came ((to the South)) to command and showed themselves to be overbearing, etc., thus bringing division into the Front ranks.”[7]

The “Chinese Card”

In 1965, a Vietnamese group purportedly emerged in the South – “The People’s Revolutionary Group of Nam Bộ”, that was critical of COSVN [8] and North Vietnam. A US report noted: “Of late, leaflets of anti-North Vietnamese character have been frequently discovered in the Viet Cong controlled areas around Saigon. These leaflets, while containing the usual tirade against the ‘US imperialists’ have denounced in unequivocal terms the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NFLSV), the (North) Vietnam Workers Party (VWP), and Communist China (CPR). … This organization, a possible splinter faction, has a flag of its own bearing a Communist red star … The growth of such a faction is natural in view of brewing discontent among the South Vietnamese cadres of the Viet Cong against North Vietnamese increasing control in the affairs of the NFLSV with the introduction of larger and larger numbers of North Vietnamese into this front organization. Ethnic, cultural and linguistic differences between the South and the North have apparently begun to show their effect on the unity of the Viet Cong.” A September 1965 three-page “Declaration” by the People’s Revolutionary Group cited the Hanoi communists’ “Lao Động ((Workers’ Party)) as sub-servient to the Chinese Communist Party” [9]

A US/South Vietnamese propaganda leaflet – depicting Chinese Control of NVA/VC

In September 1966, the Joint US Public Affairs Office (JUSPAO) in Saigon issued “guidance for a psychological offensive” to promote the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong as being “instrumentalities of an international conspiracy and of Red Chinese imperialism.”[10]

Leaflet: US 245th Psyops Company – Nha Trang, 1967 [11]

Tensions Between Northerners and Southerners [12] – and “Central Vietnamese”

The regional origin of an NVA and VC cadre or soldier (ie as a Northerner, Central Vietnamese, or a Southerner – with mutually intelligible dialects) was easily identified by his accent – ie variation in “sounds and tones” and vocabulary.[13]

US CIA reporting noted early “bureaucratic and regional tensions” within COSVN. “The best documented controversies in COSVN have centered on regional or sectional prejudices and resultant complaints over favoritism within the bureaucracy. Reliable reports of cleavages along geographic lines began to accumulate as early as 1957, before COSVN had formally surfaced. During this period, numerous northern-based [sic] regroupees and cadres who had remained in the South became exercised over what they saw as a tendency in Hanoi to reserve key promotions for native North Vietnamese. … The step-up in infiltration in the early 1960s apparently fuelled still other regional prejudices within the COSVN. The assignment of many infiltrators to Central Vietnam reinforced speculation down the line that this area was being favored by planners in Hanoi. Traditionally, there has been little love lost between Central Vietnamese, natives of the Saigon area, and the ((Mekong)) Delta, and their antagonism most likely carries over into the Communist hierarchy. Late in 1963, under the pressures of infiltration, this hostility reportedly broke out into the open. Several COSVN figures from Saigon accused the Central Vietnam contingent of ‘boot-licking’ and monopolizing promotions. The Centrists – backed by recent North Vietnamese arrivals, retaliated by mounting a campaign to oust their frequent critic, Tran Bach Dang, the chief of COSVN’s Propaganda and Training Section.” … COSVN rivalries took on an even more distinct North/South coloration in 1965 when the first large contingent of conventional North Vietnamese troops arrived.”[14]

Early in the War, a 1966-67 US study[15] on NVA/VC “cohesion” assessed however that: “almost throughout, the ((NVA/VC)) enemy tends to have no doubt about the righteousness of his mission: Northerners in no way seem to regard their presence in the South as an aggression since they consider both Vietnams to be ‘one country of brothers’; and both Northerners and Southerners seem to feel that their struggle against ‘the Americans’ is not merely justified, but a national necessity.”

However, in the South, there was discord within communist units between North Vietnamese and Southerners – and negative attitudes by Southern civilians to Northerners, were expressly noted in several captured VC directives.[16]

To counter increasing tensions between NVA and VC personnel, the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN)[17] felt it necessary to issue Directive No.84/CV-B1 in December 1967 urging the “fraternal” treatment of newly-arrived Northerners. The Directive noted “regrettable mistakes” in the treatment of Northern troops – who had been disparagingly called “doltish, clumsy, and slow-moving”, with “fun being made of their accent” ((for the different Vietnamese language dialects, and complaints made of the Northerners as “lacking experience.” It recognized some of the reasons that the Northerners might appear to be different from the local combatants: “Because they are strangers to the area, the environment and the people, and because their speech is sometimes not the same, and because their health is somewhat poor.”[18]

A June 1968 directive by the Military Affairs Committee of the South Vietnamese Liberation Army addressed similar themes. “For the sake of our sacred duty toward the Fatherland and for the independence and freedom of our entire country, our ((Northern) comrades, our kith-and-kin brothers, have sacrificed everything, including their own lives. … Because they are strangers to the area, the environment and the people, because their speech is sometimes not the same as ours and because their health is somewhat poor, these comrades, these brothers of ours, have appeared to be estranged and slow moving. … among us there are a number of people who – in their comments, have labelled these ((Northern)) brothers as doltish, clumsy, slow-moving etc or have made fun of their accent. … there are a small number of traders who have taken advantage of these ((Northern)) brothers’ clumsiness and lack of experience to exploit them heavily. For instance, they sold food to the Southern brothers at 100 piasters a kilo – but as soon as these customers left the shop, they charged the Northern brothers 110 or 115 piasters for the same amount of food.”

A 9th VC Division directive included: “Absolutely avoid friction, authoritative attitude, disrespect, arrogance, and division between South Vietnamese and North Vietnamese and between ethnic minority peoples, and prevent desertion.”[19] That directive also alluded to dietary differences eg; Southerners did not eat dog meat – “a Northern taste”.[20] Northerners ate their vegetables cooked – while Southerners preferred such uncooked.

In early 1967, a report [21] by the South Vietnamese National Intelligence Center – based on interrogations of VC cadre in Kiến Tường Province (an “upper” Mekong Delta province), listed “Discord Between the NVN and SVN VC Cadres” – citing 20 “discordant reasons” (“A” to “T” inclusive) for tensions, see Annex A.

The Northerners also had criticisms of the southern Việt Cộng [22] – complaining that “old SVN-born cadre had conservative thoughts, were lazy in studies, and erroneously considered their war experiences and achievements on the battle-front as the most important. So they have erroneously under-estimated the knowledge of younger NVN-born cadre.” (9th VC Division, 1972).

A senior NVA defector – Lieutenant Colonel Lê Xuân Chuyển [23], also spoke of rifts and arguments between Northerners and Southerners – citing their differences in “personalities and lifestyle” as a source of tensions – and characterising Northerners as “disciplined and mindful” while Southerners were “liberal and free” … contradictions between the Northern and Southern cadre are really hard to solve.”[24]

After rallying in August 1966, Lieutenant Colonel Chuyển also made several criticisms highlighting divisions and conflicts between Northerners and Southerners including: “For example, there was a VC ‘Thượng Tá’ ((Senior Colonel)) – which is the executive officer for a division. This man was a Northerner who came to the South and was proposed as executive officer in the forces of the South Viet Nam Liberation Front. He was to be Executive Chief of Staff. The Southerners did not accept this, and they proposed a major from the South for that position who had no experience and had worked for the intelligence service. … I would like to give you another example of this phenomenon. I know one case in the South of a platoon leader who was proposed to be a regimental commander. This man had fought against the French. He was proposed as a regimental commander because he was a Southerner. Because of him, too many VC were killed by the other side. The Northern cadres always lead very orderly and strict lives. The Southerners are too free from the point of view of their thinking, and they change their minds very frequently. Their morale also fluctuates. One day they might have high morale and the next day they may be very passive. They do not have enough discipline and they do pretty much what they want. They do not follow any orders.”[25]

In October 1966, a JUSPAO guidance paper [26] noted: “There is friction between Northerners, Southern regroupees, and Southern VC cadre. Many bitter comments were made concerning this. Said a typical Southern cadre: ‘The returnees consider the South Vietnamese cadre their lackeys. They are very arrogant, and I have been ordered by them to do this or that … We southern cadre endured hardships for years while they were enjoying themselves in the North, and now they come to command, show themselves to be overbearing and bring division into the Front’s ranks’.”

In its conclusion, the 1967 Simulmatics’ study for the US Army [27] noted: “Despite these points of friction, it must be emphasized that working relationships between Northerners and Southerners are generally more-or-less harmonious. Most respondents ((ralliers)) emphasized common goals over regional rivalries and – as one, rather well-informed ex-cadre from the South suggested, the policy of making Northern personnel at least nominally subordinate to Southerners serves to minimize potential Southern resentment, though it doubtless creates ill-feeling among Northerners.”

A July 1967 JUSPAO study related: “In individual cases there is a known persistence of stereotyped ideas not uncommon among Vietnamese in general – ideas of Northerners as cold and aggressive, for example, or of Southerners as indolent and pleasure-loving. Among the Viet Cong, expression of these ideas often takes the form of complaint by Southern cadres that Northerners are arrogant, domineering and overly strict. Northerners, on the other hand, sometimes criticize their Southern comrades for being indisciplined, dilatory and too easy going. On each side, jealousies over rank, promotion and position are occasionally linked with accusations that preference has been shown ((to)) a rival because of his regional origin. … A few Southern Viet Cong are known to have voiced suspicion that the North may sacrifice their interests in future settlement of the war. … Such animosities and suspicions, however, are not known to have run deeply enough so far to turn troops against their commanders, impair the effectiveness of fighting units or cause any major rejection of North Vietnamese authority where it is exercised directly in the South.”[28] However, that JUSPAO guidance on exploiting “North-South Regionalism” cautioned to: “Guard against magnifying issues or giving a regional interpretation to disputes which may in fact represent simple personality clashes or problems between higher and lower cadres attributable to other causes. … In addition to the above cautions on accuracy and careful handling, note the emphasis on localized effort. Aim any messages straight at the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese targets concerned – at specific units or individuals. A national campaign seeking to play on sectional prejudices is not in our long-range interests and would run counter to the present National Reconciliation Program of the Government of Vietnam (GVN).”[29]

Within the 275th VC Regiment, tensions were reported in Phước Long Province in late 1967 after it had received recently received reinforcements from the North. During his interrogation, the POW Trần Văn Lân (Northerner – 9th Battalion, 275th Regiment) related that there were: “Overt schisms between the North Vietnamese soldiers and the South Vietnamese cadre in the unit.”[30]

In late April 1968, tensions between NVA and VC were indicated in a VC document [31] that was recovered by the US 101st Airborne Division in Bình Dương Province (north of Saigon) instructing subordinate communist units and agencies of “B1” that necessary action must be taken to stop the discrimination against NVA troops. The document related: “Recently a number of our ((Northern)) comrades and young draftees have come to our area on missions. This is a very encouraging fact because it illustrates the kith-and-kin ties which bind the North and the South into one family, ((whose members)) join forces to destroy the enemy and avenge the country. This increases our force and gives us encouragement and added strength, thus helping us defeat the American aggressors and their lackeys more quickly in order to liberate the South and unify the country. … Our correct attitude, as befits the local combatants, is to show love and to extend assistance and protection to these comrades and brothers of ours, to whom we are bound by kith-and-kin ties as well as class ties. It is our duty to show these sentiments through our words, our behavior, and our concrete deeds. … However, among us there are a number of people who in their comments haye labelled these brothers as doltish, clumsy, slow-moving etc or have made fun of their accent. In one unit, some of these brothers, while on a supply-carrying mission, got lost because of an alert. When they managed to rejoin their unit, they showed much pleasure. However, the unit commander scolded them publicly in these terms: ‘Whose pants have you been washing, which kept you so late.’ Among the people in general, there are many who do not truly show an understanding of these brothers. Some of these brothers have confided, ‘the mothers and sisters are too indifferent to the troops.’ … The words and behavior mentioned above are regrettable mistakes. Although they reflect the concept and actions of only a few among our ranks and among the people in general, they nevertheless prove that our ideological and political indoctrination is still weak.”

In early 1969, NVA POW Captain Trần Văn Tiểng – the assistant political officer of the 3rd Battalion/275th Regiment [32] assessed: “About 80% of the Regiment’s total strength was NVA and about 20% were VC or regroupees.” No specific examples of discord within the 275th Regiment can be specifically cited. However – as noted earlier, a HQ 5th VC Division rallier – NVA Lieutenant Colonel Lê Xuân Chuyển, made several references to discord and tension between Southerners and Northerners in the 5th VC Division.

In Phước Tuy Province, difficulties were also reported between the D445 Local Force Battalion and the “Northern” D440 Battalion – previously the NVA “Bắc Ninh Battalion” that had infiltrated into the South in September 1967. A rallier from D440 in May 1970 reported that D445 and D440 battalions were “not willing to cooperate with each other because of conflict between SVN (South Vietnam-born) and NVA troops.”[33]

In 1972, a VC rallier from Phong Dinh Province (central Mekong Delta region) – who had “regrouped” to the North after the 1954 Geneva Accords and subsequently infiltrated into the South, described “Divisiveness” among VC and NVA personnel and units. Kiểu Công Quển related [34]:

“Dissention between PAVN cadres from the North and PLAF cadres from the South grows steadily higher. From company commanders down to privates there is a great deal of partisanship and envious thinking, by both Northerners and Southerners. … A serious rift developed in my unit in 1971 and the division remains today. Southerners nicknamed the Northerners ‘French citizen’ and some did not want to as sociate with them. For example, a group of Southerners would be talking – and a Northerner would approach. One of the Southerners would say, ‘Quiet, here comes a citizen of France’. Some Southerners and Northerners would associate with each other, Still other Southerners would say to Northerners, ‘The only thing we have in common is the Party view and policy of resisting the U. S. imperialism and feudalism. We cannot associate. … … Southern cadre, even ranking ones, have little authority since they are not Party officials, only rank and file members. So they become dissatisfied. The result is quarrelling, frequent scuffles, rancor and other undisciplined acts; the desire to desert, go away, get married and live as civilians. This means of course they would be condemned as betrayers of the Revolution regardless of their previous contributions to the Revolution.”

In his debriefing in 1974, a VC rallier from the 9th VC Division related “disunion” in the Division caused by disputes between VC and NVA personnel. He noted that the 9th VC Division “was commanded by cadres returning from the regroupment area (cán bộ hồi kết) and had only SVN youths in its ranks. Gradually its strength deteriorated to be replenished by recruits coming from the North. So there has been the disunion between North and South elements in this Division. In recent years, The Communist 9th Division had to continuously participate in combat. A great number of SVN-born cadres were killed to be replaced by cadres tumultuously [sic] coming from NVN. So, most of units in this Division have been commanded at present by NVN cadres. As a result, the disunion between North and South elements has become more and more serious.” He stated that “differences in regional customs and traditions between the North and the South have created a part of (the) difficulties in the internal activities of each separate unit”; and the worsening “mutual hatred between most of NVN and SVN-born cadres and soldiers. … one can clearly see two main clans: The NVN-born clan and the SVN-born clan. They have conversation time, tea parties, and banquets separately from each other. They never sit in a common table. … SVN-born cadre were not only rejected, but also insulted by NVN-born soldiers and cadre.” In conclusion, the rallier noted: “This disunion between North and South has been seen in most units in the 9th Communist Division. The Headquarters has known about this fact, but has been unable to prevent it effectively …”[35]

Exploiting Tensions and Differences

In a late-1965 “Guidance” directive [36], the US JUSPAO organisation in Vietnam was initially more cautious and circumspect in exploiting any divisiveness among the communists in South Vietnam:

“We search for hard evidence on political and sociological divisions and ruptures within the ranks of the National Liberation Front or Viet Cong, and the PAVN elements in South Vietnam. … We refrain for the moment from attempting to exploit these divisions on a national level because of current inability to present a strong and credible case. If such evidence should become available, for example through the defection of a high level enemy official, appropriate exploitation will probably be undertaken. We do not at this time intend to exploit regional differences, for example Northerner vs. Southerner. We do not exploit ethnic minorities, for example, Vietnamese vs. Chinese. We do not intend to exploit religious differences, but of course do exploit any evidence of anti-religious or atheistic behavior on the part of the communists. … It should be recognized that there are good possibilities of tensions developing in Viet Cong/PAVN ranks but that evidence is not yet sufficiently conclusive, and, based on circumstances, it may become necessary to exploit any or all forms of tension.”

However, six months later, JUSPAO guidance was more aggressive: “Contradictions and Cleavages – Northerner Versus Southerner [37]: Within the Viet Cong organization exist certain differences and cleavages which Communists call ‘contradictions’. Some are inherent in the nature of Vietnam’s geography and population. There are basic differences between Vietnamese in the North, the South and the Center. These sectional differences involve long-standing rivalries. The northerners, who have had considerable infusion of Chinese blood are noted for their aggressiveness, energy and sense of superiority toward the southerners whom they regard as indolent and inefficient. In the South, the climate is more tropical, there is more rich soil and less population congestion … . Southerners look upon the northerners as grasping and aggressive and fear falling under their domination. Knowing the relative overpopulation and poverty of the North, the more prosperous southerners fear the South would be bled dry to support the hungry North. … These sectional differences have created frictions among the Viet Cong. The older Viet Cong leaders, former Viet Minh who were ordered to stay in the South and go underground in 1954, kept the Party going during trying years. They resent the return of the ‘regroupees’ who went North in 1954 for retraining and returned to the South to give orders. Even more do the southerners resent the northerners who came from Hanoi without experience of guerrilla warfare under the conditions in the South but still tell the southerners how to fight the war.”

In December 1967, a JUSPAO policy paper [38] again noted: ““Indications of divisive tendencies spotted among the VC in earlier studies continue and involve a certain amount of’ friction between Northerners, Regroupees and Southern cadre, the former two being considered overbearing by the Southerners. … the increased integration of Northern cadre and NVA officers into understrength main force VC units might even have accentuated these stresses.”

However, a US MACV “Guide” issued in April 1968, indicated a continuing caution by the US and the South Vietnamese in citing divisions between VC and NVA troops in PSYOPS propaganda material – eg: “Another source of foreignness in propaganda is the inadvertent admission of foreignness in ‘wedge driving appeals’. One leaflet attempting to exploit reported friction between the North Vietnamese and the South Vietnamese stated, ‘You South Vietnamese are looked down upon by the North Vietnamese,’ making it obvious that the propaganda source was neither North Vietnamese nor South Vietnamese, but a foreigner.”[39]

In 1969, the Joint Propaganda Development Center issued a psychological warfare leaflet with the specific theme of “Division between the VC/NVA”[40]:

Content: Exploiting Disagreement between the VC and North Vietnamese Main Force troops.

“To Southerners in the Communist Ranks. It is normal that every soldier must fight, but you have fought longer than anyone else and the hardships you have endured have been most severe. For many years you have lived under the constant threat of the artillery, jets, helicopters, rockets and other operations. However, your previous experiences were denied by a group of young men from the North. These Northern infiltrators have portrayed themselves as your ‘brothers’. Now you have to obey their orders.

Ask this question: What superiority do these infiltrators have over you? Their endurance and experience must be tested for a long period of time to see if it is comparable to yours. Ironically, you are now only second fiddle in this war. These strange guests have become your masters and they hold the key positions. Is it your job to be first in battle, dying there – or having to produce food at the rear base to feed them? Be sincere enough to find out what the true answers to these questions are. Your fate depends on these answers!”

*******

In May and June 1969, MACV reported on “Friction Between NVA and VC Troops” in III CTZ an IV CTZ and cited examples [41]:

“A rallier, a former VC platoon leader, reported that half of his unit was NVA. A prominent point of friction was the terminology used by one group to the other. If the VC used South Vietnamese dialect frequently the NVA troops would correct them, much to their annoyance. The VC enjoy eating some vegetables raw while the NVA troops wanted them boiled. Another cause of conflict was that NVA troops when they initially arrived in RVN were inexperienced in battle and unfamiliar with the terrain. Hence, the VC led the attacks, reconnoitred targets and planned ambushes for the NVA to conduct. Another rallier, a political officer, reported that there was considerable animosity between NVA and VC officers. NVA officers received better training than the VC and, hence, felt superior to them and let them know they considered them stupid and tactically incompetent. However, the VC were more familiar with the terrain and consequently there was continual disagreement among both groups as to who should command the combat operations. Directives from higher headquarters generally resolved this disagreement. There was no social rapport among the officer ranks.” A VC political cadre noted NVA within his unit “held extreme prejudices because most North Vietnamese were better educated and more literate than the VC.” “Another source of conflict was that VC got mail and NVA did not.[42] NVA told VC of the good life in NVN also.” A NVA soldier captured in the Seven Mountains area (IV CTZ -Mekong Delta) related that: “The majority of the NVA had been drafted and saw little chance of returning to North Vietnam. The cadre in the unit were generally VC and the lower ranking personnel were NVA. Constant friction arose between the two groups, which the NVA attributed to the VC’s tendency to be rude and disrespectful. Most of the NVA found it difficult to adjust to the heat of the Delta and were further inconvenienced by the lack of potable water. They were further disheartened by the lack of trees to shield them from aerial observation.”

“USMACV closely followed reports of NVA versus VC dissension and friction. At a weekly intelligence conference on 20 September 1969, General C.W. Abrams (COMUSMACV) remarked: ‘Christ, you can’t get them ((NVA and VC)) together at a free beer party, really.’ ” [43]

*******

In January 1970, MACV psychological operations policy[44] noted: “Divisiveness among the VC continues to indicate a certain amount of friction between northern, southern, and regroupee cadre; eg the northerners are considered overbearing by the southerners.” However, the exploitation of such friction was qualified:

“Thematic appeals with respect to the exploitation of divisiveness are not to be allowed to impair the overriding task of nation-building. These appeals are to be confined to activities and areas strictly within the enemy ranks and not to those social factors which spill beyond the ranks of the enemy. For example, differences between communist leaders and communist followers can be legitimately exploited. Differences which arise from regional, ethnic, or religious differences are not to be exploited. … Generally, divisive messages are to confine themselves to a statement of the facts, allowing the chemistry of the situation to do the rest of the work.”

********

Later in the War, the US was more aggressive in exploiting North-South tensions – particularly to further advance the successful Rallier/Returnee/Hồi Chánh Program – ie the Chiêu Hồi Program.[45] From 1969, the Saigon Government actively sought to exploit differences and tensions between Northern and Southern communists – as evidenced in the text of an August 1973 radio broadcast [46]:

“The facts that have been revealed – more and more, extensively show that conflicts and discrimination between northerners and southerners within the treacherous organization called the Liberation Front have become more acute than ever before. Freedom-seeking communist cadres and soldiers have confirmed that the discrimination between southerners and northerners has become more acute, because the overbearing and arrogant North Vietnamese communist cadres and soldiers have almost openly looked down upon and castigated the southern cadres and soldiers for being unable to hold captured territory. Conversely, the deceived southern cadres and soldiers have accused the northern communist cadres and soldiers of being unpopular and bloodthirsty, acting overbearingly and alienating the people in areas under temporary communist control.”

While a number of statements and the written texts of a few leaflets and pamphlets have specifically cited “oppression” of VC elements by “overbearing and arrogant Northerners”, no US or South Vietnamese leaflet, pamphlet or poster has yet been noted by the author (Chamberlain) attempting to exploit VC v NVA tensions that includes a sketch, drawing, or illustration of such tension or conflict between the VC and the NVA. It appears that the “avoidance” of such depictions was probably a conscious policy by the US and the South Vietnamese.[47]

****

The major US study – The Pentagon Papers, also addressed the issue of “North versus South” [48]:

“The monopoly of Viet Cong leadership by the infiltrators from the North became evident after 1960. By 1965, they were clearly dominant. For example, while southerners still controlled the Viet Cong of the Mekong Delta, in the provinces just north of Saigon – Tay Ninh, Binh Duong, Binh [sic ie Bien] Hoa, and Phuoc Tuy [49] especially – regroupees and northerners had assumed most of the principal command positions. A document captured in January 1966 listed 47 VC officials attending a top-level party meeting for that region, of whom 30 had infiltrated from 1961 through 1965. Seven of these all holding high posts in the regional command were North Vietnamese. … At Viet Cong central headquarters in Tay Ninh – Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) – Senior General Nguyen Chi Thanh of the NVA and Major General Tran Van Tra [50] of the NVA and the Lao Dong Central Committee, his deputy, both North Vietnamese [sic], held the top positions in the Communist party Secretariat under which there was a Military Affairs Committee heavily weighted with North Vietnamese military officers. … By 1966 it was clear that in the northern provinces of South Vietnam, the NVA was in direct command.”

Northerners and Southerners – how many ?

In September 1968, a US CIA report assessed the 275th Regiment’s strength as “65% North Vietnamese”.[51] A captured 5th VC Division document – dated 25 September 1968, listed the personnel strength (probably of the 5th Division) as 6,436 – which included 1,279 in A55 (probably the 275th VC Regiment); 1,133 in A56 (probably the 88th NVA Regiment); and 1,468 in A57 (the 33rd NVA Regiment) – 845 additional personnel were to be recruited in the subsequent month.[52] As noted earlier, in his extensive debrief in February 1969, NVA Captain Trần Văn Tiểng (see footnote 31) stated the 275th Regiment’s total strength was 1,600 (combat 650, support 800, rear services 90) – of whom 80 percent were NVA and 20 percent were Southerners (including regroupees – ie cán bộ tập kết, that had been trained in the North). During the War, Hanoi denied the presence of PAVN troops in the South.[53]

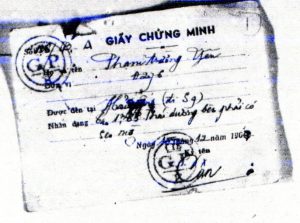

“Identity Card” – ie Infiltration Pass dated 15 December 1967 Phạm Trường Yên – 275th Regiment[54]

Following the January 1973 Cease Fire, a major US report optimistically assessed in mid-1974: “Finally, morale problems also are beginning to contribute to the overall constraints on communist capabilities. According to various sources, Southern troops and cadre are becoming restive under NVA domination in the inconclusive ceasefire environment, and Northern personnel are becoming increasingly disturbed at the willingness of their southern comrades to squander assets – particularly North Vietnamese assets.”[55]

Post-Liberation in April 1975 – according to the memoir of a former PRG Justice Minister Trương Như Tảng – a Southerner, the Northern communist leaders discriminated against the Southern organisations and cadre, disillusioning many Southerners.

Post-Liberation in April 1975 – according to the memoir of a former PRG Justice Minister Trương Như Tảng – a Southerner, the Northern communist leaders discriminated against the Southern organisations and cadre, disillusioning many Southerners.

Through the late 1970s to the late 1980s, for many NVA and VC soldiers (now all “People’s Army of Vietnam” – PAVN), fighting continued in Cambodia against the Khmer Rouge – including for the 275th Regiment. In 2016, a short article on the history of the 275th Regiment noted that during the Wars: “The Regiment had suffered 4,860 of our comrades killed – including 890 killed in Cambodia, apart from those who were wounded.”[56] This is a very heavy casualty rate for a regiment whose strength averaged about 900.

A large number of Northerners – who had served in NVA/VC/PAVN units in the South and Cambodia, remained in the South after their military service – attracted by the economic opportunities. The 33rd NVA Regiment has an active association in the South, with a memorial at Bình Ba – the site of its battle against 1 ATF elements in June 1966.

NVA/VC Cooperation in Phước Tuy – June 1969: Attacks on Bình Ba and Hòa Long [57]

As an element in the Communist’s June 1969 “High Point Campaign”, two battalions of the NVA 33rd Regiment were tasked against the village of Bình Ba about six kilometres north of 1 ATF’s Núi Đất base – and were engaged on 6 June by 1 ATF’s Ready Reaction Force: D/5RAR (Major Murray Blake), M113s, and Centurion tanks (Operation Hammer). In coordination with the 33rd Regiment’s action, the VC’s Châu Đức District Unit was to attack the village of Hòa Long just south of the Núi Đất base. However, the advance of the District Unit’s C-41 Company elements[58] was disrupted enroute by Australian forces, and it did not enter Hòa Long until 7 June 1969 – and was driven out by during 1 ATF’s Operation Tong (C/5RAR – Major Claude Ducker).

The Party Committee of the 33rd NVA Regiment giving orders for an attack.

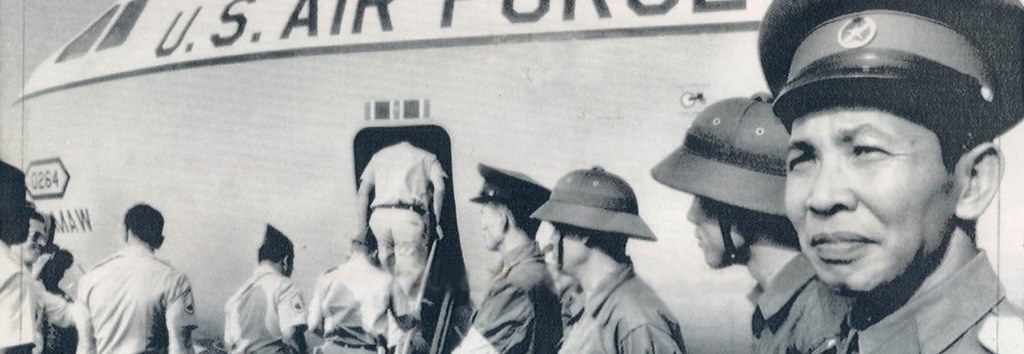

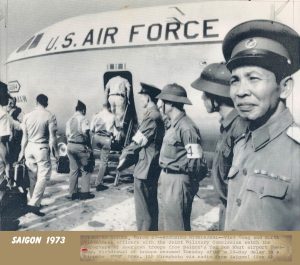

NVA (PAVN) – in caps, and VC (PLAF) cadre – in pith helmets – of the Four Party Joint Military Commission monitor US military personnel departing Vietnam.

Tân Sơn Nhứt airfield – Saigon, 27 March 1973

Victory Parade – Saigon, 15 May 1975 – NVA (PAVN) Tanks

“Post-Victory Tensions”

Post-Liberation in April 1975 – according to the memoir of a former PRG Justice Minister Trương Như Tảng – a Southerner, the Northern communist leaders discriminated against the Southern organisations and cadre, disillusioning many Southerners. At the 15 May 1975 victory parade in Saigon, the NVA (PAVN) wore new hats while the VC were “unkempt and ragtag” under the DRV flag – according to Trương Như Tảng. Viewing the parade, Tảng asked where were the 1st, 3rd, 7th [sic] and 9th VC Divisions?” PAVN Commander General Văn Tiến Dũng replied with “a wry smile” – “unnecessary as we are already unified.”

In August 1975, at a Party meeting, the Vietnamese leadership decided to dissolve the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) – without consulting the PRG. In mid-July 1976 – with the disbandment of the PRG and the National Liberation Front (NLF), Trương Như Tảng queried whether at least a “funeral celebration” was appropriate. The Hanoi leadership agreed – and a small function was held later that month at the Rex Dance Hall (Vũ trường Rex) in Hồ Chí Minh City (ie Saigon until 3 July 1976). Only 30 cadre were present (ie PRG, National Liberation Front, and Southerners of the Alliance of National, Democratic, and Peaceful Forces).[59]

Annex A

National Intelligence Center, Interrogation Report, No. 121/67, 14 February 1967.

VCATT Item No. F034600422579, see footnote 20.

Annex B

US MACV/RVNAF, The Disunion Between North and South Elements in the Communist 9th Worksite Division, April 1974. VCATT Item No. 231051302114 (see footnote 33).

“Formerly the 9th Work Site Division was a large-size unit of V.C. in the South. From the “Spontaneous Uprising Stage” day to the period when it became a relatively improved division in the years 1964, 1965 through the Bình Giã, Đồng Xoai, Lộc Ninh campaigns etc. This Division was commanded by cadres returning from the regroupment area (cán bộ hồi kết) and had only SVN youths in its ranks. Gradually its strength deteriorated to be replenished by recruits coming from the North. So there has been the disunion between North and South elements in this Division.

In recent years, The Communist 9th Division had to continuously participate in combat. A great number of SVN-born cadres were killed to be replaced by cadres tumultuously [sic] coming from NVN. So, most of units in this Division have been commanded at present by NVN cadres. As a result, the disunion between North and South elements has become more and more serious.

Fearing that they would lose leading positions, and the rights to decide important things in the guidance, SVN-born cadres have had competitive tendencies against NVN- born cadres to dig more deeply the internal disunion ditch to heighten the prestige of their clan. Moreover, a number of old-SVN born cadres have had conservative thoughts, been lazy in studies, erroneously considering their war experiences and achievements on the battlefronts as most important. So they have erroneously under-estimated the knowledge of younger NVN-born cadres. In addition to that, the differences in regional customs and traditions between the North and the South have created a part of difficulties in the internal activities of each separate unit.

At present, the disunion Between North and South elements has occurred in most of units in this Division under following forms:

- In conflicts to the election of the Party. … … In 1971, in the Conference of the Political Office Party Committee/9th Division, NVN-born Lieutenant Colonel Dong Thanh Lan – Chief Of the Political Office, presented himself as candidate for a position in the Party Executive Committee. But he failed because the majority of party members were born in SVN. Later. the 9th Division Headquarters had to transfer Lieutenant Colonel Dong Thanh Lan to another unit and designate an SVN-born cadre to replace him.

- Conflict in position. … … The disunions between North and South cadres and soldiers have become more and more serious when there have been overt conflicts contrary to the ‘North and South Union Spirit’ and the ‘Immediate Mission To Struggle Against Enemies’. These disunions and conflicts have been so clear that the struggle morale and union spirit in most of units nearly deteriorated. A typical case was that in June, 1972, after Hai Thiet – ranking regiment commander and field-grade political officer in the 1st Regiment/9th Division, was killed in the Bình Long Battle (when there was rumour that he would be designated soon as Assistant Chief of the Political Office – 9th Division). The 9th Division Headquarters designated a NVN-born cadre (Lieutenant Colonel/Political Committee/COSVN) to replace Hai Thiet. But all SVN- born cadres in the 1st Regiment opposed this order. Worse than that, some dared to send a letter to the 9th Division Headquarters to request that this NVN- born field-grade political officer be removed immediately. As a result, a SVN-born field-grade political officer was selected by the 9th Division Headquarters to replace the above NVN-born new-comer. The above fact has worsened the mutual hatred between most of NVN and SVN-born cadres and soldiers. And the NVN-born cadres and soldiers have complained about the incompetence of the 9th Division Headquarters in solving this problem.

At present, in the 2nd Regiment/9th Division – Le Giao (ranking regiment commander – a cadre who had returned from regroupment to NVN – ie: cán bộ hồi kết), had a serious discrimination spirit – distinguishing NVN elements from SVN cadres. When reading the list of cadres proposed for promotion – submitted to him for approval and signature by political cadre in the Regiment staff, he usually asked before examining each separate case: ‘Was he born in the North or in the South?’ This question made many NVN-born cadres very discontented. They expressed their opposition by ceasing the struggle or requesting transfer to another regiment.

- Conflict about women. In most of units in the Communist 9th Division, except in study meetings and in daily activities, one can clearly see two main clans: The NVN-born clan and the SVN-born clan. They have conversation time, tea parties, banquets separately from each other. They never sit in a common table. In some units having the ‘fair sex’ the disunion becomes more serious, the female SVN cadres and the Vietnamese residents in Cambodia usually like to make friends with NVN-born cadres and soldiers. Due to this reason, SVN-born cadres and soldiers search for means to calumniate ((ie to make false or defamatory statements)) against their opponents. They slander that NVN cadres and soldiers are cunning and attempt to deceive the fair sex to have illegal sexual relations to satisfy their bad thirst for carnal pleasure – the sooner the better. In diverse party chapters or Unit Commanding Boards having a majority of SVN-born cadres, NVN-born cadres and soldiers have to bear revenges with the unjust judgments, observations, evaluations, merciless slanders and criticisms etc. Worse than that, SVN-born cadres search all means to create contradictions, disunions between NVN-born cadres and the above female SVN-cadres. In case of failures, SVN-born cadres use the power of Unit Party Chapters or Unit Party Committees – or that of higher-ranking authorities in the agencies or units concerned, to menace NVN-born cadres and soldiers. SVN-born cadres can also use political interests to purchase [sic] their colleagues and ask them to harm NVN-born cadres and soldiers. Due to this reason, a number of female cadres born in SVN have unjust bad prejudices about NVN-born cadres and soldiers so that they search all means to live far from the above slandered victims. Once, from other units, a number of NVN-born cadres and soldiers came to visit a number of female cadre born in SVN who were working in the PSYWAR Entertainment Group. They were disturbed by SVN-born cadres not to have contact with the above said girl-friends. When being told about this bad fact, NVN-born cadres became angry, stopped all visits, and searched all means to revenge. So when the Psywar Entertainment Group came to perform plays in concerned units, SVN-born cadre were not only rejected but also insulted by NVN-born soldiers and cadre. In the 33rd Health Battalion/9th Division, Ba Kho – its commander, was rather old but had a SVN-born young wife and children. He had a serious spirit to discriminate and to distinguish NVN elements from SVN cadres. A number of NYN-born cadres and soldiers searched all means for revenge, and let a NVN handsome person flirt and seduce his young wife. Desperate after losing his wife, Ba Kho became love-sick and worked negligently. His position was shaken. Later, he knew the truth, and tried to re-educate his wife. Then he secretly took revenge against his NVN-born subordinates. His wife did not return to his house – though having common children with him. As a result. the disunion between North and South elements in this Battalion became more and more serious. NVN- born cadres have been badly considered by SVN-born cadres as ‘Tay’ or other dirty names. Vice-versa SVN-born cadres have been called: ‘ignorant’, ‘Ethnic Minority’ and ‘Savage People’ by NVN cadres.

- Conflicts leading to fights. In many units, the disunion between North and South elements has reached the climax. Many persons, oppressed for a long time – unable to master their discontent, took advantage of favorable occasions to beat their opponents so as to appease their anger. On the Tet days in 1971, when the 22nd Artillery Battalion/9th Division was camping in the Chup rubber plantation in Kompong Cham Province (Cambodia), NVN-born cadres and soldiers in this unit were usually oppressed by a number of SVN-born cadres in the Battalion Commanding Board. They were extremely angry but had no means to report this fact to the higher-ranking authorities to solve this injustice. On this Tet occasion, they bought alcohol and dishes of food in great quantity to organise a great banquet on the 1st Tet Day. They invited a number of SVN- born cadres to participate in it. As pre-determined, they drank alcohol, feigned themselves intoxicated then beat mercilessly and seriously wounded their SVN-born guests. Many victims had to live temporarily in other units to wait for the interference of higher-ranking authorities. Later, this event was reported to Colonel Ham Phong – political officer of the Division, who could not solve this conflict. NVN-born cadre and soldiers defended themselves by declaring that they had taken those actions after being intoxicated. As a result, series [sic] of SVN-born soldiers were transferred to other units to avoid future revenge attacks.

One day in April 1971, the Source ((name omitted)) and a number of NVN-born friends came to Tapao market in Kroch Chhmar District, Kompong Cham Province ((Cambodia)) for an operation along with a large radio set. At about 1100hrs, they reached this market, and entered a tea shop where they listened to the ‘Liberation Broadcast Station’ and the ‘Renovated Theater Play’ (Cải Lương). A moment later, a group of SVN-born cadre entered. They had another radio set to listen to “The Old Music” (Ca Nhạc) performance on a more sonorous channel. To listen to the sounds more clearly, the Source and his NVN-born friends listened to the “Hanoi National Broadcast Station” and the “Noisiest Old Comedy” performance (Cheo Cổ). Before this action, SVN-born cadres cried loudly, condemning the Source and his NVN-born friends for discourteous attempts – deciding to break their large-size radio set. A noisy disputation occurred to reach near a fight with gun explosions. Fortunately, two higher-ranking cadre arrived by Honda, and they ordered both sides to disarm.

Measures to Prevent This Disunion

This disunion between North and South has been seen in most units in the 9th Communist Division. The Headquarters has known about this fact, but has been unable to prevent it effectively – even through the following measures:

Party Chapters, Party Committees, and all units concerned must continuously organize study meetings to heighten the Union Spirit between North and South elements with the slogan: ‘Using Party members as Examples to let the People Follow Them’.

If there is disunion between North and South in any unit, the Party Committee and the Unit Commanding Board should prevent it immediately, solve it sooner the better, so that it will not be seen by others on the outside. All individuals and collective organizations committing the faults relating to the disunion between North and South elements should be severely punished in accordance with discipline.”

Notes:

[1] For “Regrouping”, see the Fourth Interim Report of the International Commission for Supervision and Control (ICSC) in Vietnam, 1 October 1955. Article 14 (d) of the July 1954 Geneva Agreement provided for a “change of zone of residence” – in a 300-day period to 19 May 1955 (extended to July 1955) – 892,876 persons formally moved from the North to South Vietnam and 4,269 from the South to North Vietnam. See Appendix IV to the ICSC Fourth Interim Report, VCATT Item No, 10390825049. Movement to the North in 1954-55 was in phases from six assembly areas in the South – including the Hàm Tân-Xuyên Mộc area.

[2] According to several official US sources, the Việt Minh leadership reportedly ordered 90,000 of its Southern troops to move to the North – see: Vietnam: Some Neglected Aspects of the Historical Record, US Congress White Paper, Washington, 25 August 1965, p.6: “Some 80,000 to 90,000 Viet Minh troops were moved out of South Vietnam in the ‘execution of the agreement’.” – VCATT Item No. 2390703004. U.S. Department of State, Aggression from the North, Publication 7839, February 1965, p.11: “an estimated 90,000” – VCATT Item No. 12050105001. USMACV, Fact Sheet 5-67, Saigon, 19 June 1967: “90,000” – VCATT Item No. 1070208010. See also Zasloff, J.J., Political Motivation of the Viet Cong: the Vietminh Regroupees, Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, May 1968. Bùi Tín – former PAVN Colonel, “Fight for the Long Haul”, in Wiest, A (ed), Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land (Wiest, A. ed), Osprey Publishing, Botley, 2006, p.56 – noted 42,000 of the regroupees to the North were military and, in North Vietnam, made up the 350th, 324th, and 325th Divisions. Bùi Tín notes that North Vietnam “did not send whole units to the South” in “1959 and early 1960”, but infiltrated selected regroupees – Bùi Tín, Following Ho Chi Minh: The Memoirs of a North Vietnamese Colonel, Crawford House Publishing, Bathurst, 1995. As noted above, some 42,000 of the assessed 80-100,000 Việt Minh regroupees to the North were reportedly military, and in North Vietnam, received military training forming eight new divisions – reportedly including the 324th, 325th, 338th and 350th PAVN Divisions. Large numbers were involved in establishing “agricultural worksites” (nông trường) in the northern border provinces and also manned the 330th Division in Thanh Hóa Province. See Zasloff, J.J., Political Motivation … op.cit., May 1968. See the detailed MACV 119-page study: North Vietnam Personnel Infiltration Into the Republic of Vietnam, CICV ST 70-05, 16 December 1970. VCATT Item No. 1071804001. See also: Bùi Tín, “Fight for the Long Haul”, op.cit., 2006, p.56. See also: Pribbenow, M.L., Victory in Vietnam, University Press of Kansas, 2002 – for the 338th PAVN Division which – comprised of southern regroupees, was converted into a training group.

[3] The 1954 Geneva Agreement: A Retrospective View, circa late 1967. A US Government document declassified on 23 April 1979. VCATT Item No. 2410403028. On the cited figure totalling “130,000” for “Southerners Regrouped North” – and its “break-up”, these figures were reportedly published in 1964 by “an Indian member of the International Commission of Control (ICC) which correspond with the totals furnished by the French and the Poles, and which appear on present evidence to be as reliable as any.” – p.16.

[4] US Intelligence – Saigon, Item 80 – Further Interrogation of NVA officer – surrendered in 1963. August 1963. VCATT Items No. 4080115001, 4080117006. For training and infiltration, see VCATT Item No. 107180400. US MACV Infiltration Study, Saigon, 31 October 1964. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v01/d392 .

[5] That first “infiltration group” of 400 men “departed Xuan-Mai on 20 February 1960 to the Do Xa base area in Quang Ngai Province (South Vietnam) and became the 70th Battalion.” US MACV Infiltration Study, Saigon, 31 October 1964. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v01/d392 .

[6] Gurtov, M., Viet Cong Cadres and the Cadre System, Rand Memorandum RM-541-ISA ARPA, December 1967, pp.25-26. VCATT Item No. 23970114001. For a listing of 78 “types” of cadre (cán bộ), see VC/NVA Vietnam Terminology Glossary (Fourth Edition), US Defense Attache Office – Saigon, January 1974 VCATT Item No. 2861408001.

[7] Zasloff, J.J., Political Motivation of the Viet Cong: The Viet Minh Regroupees: Memorandum RM-4703/2-ISA/ARPA, The Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, May 1968. The Memorandum includes interviews of 71 regroupees – “middle-level and low-level cadre”. VCATT Items No. 2311708001, 2311707027.

[8] The Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) – directed from Hà Nội and located in the Cambodia/South Vietnam border area north-west of Saigon, was the communists’ political and military headquarters responsible for Vietnam south of the Central and Southern Highlands. For detail see footnote 16.

[9] US source, Possible Rivalry between Viet Cong Units, 16 March 1965. VCATT Item No. 2311702012. It is highly likely that the “The People’s Revolutionary Group of Nam Bo” was a “black” PSYOPS operation conducted by US MACV. For the “Declaration of the People’s Revolutionary Group”, 23 September 1965 – see JUSPAO – VCATT Item No. 2311007019. The People’s Revolutionary Group appears to have been somewhat similar in concept to the “Sacred Sword Patriots’ League” (Gươm Thiêng Ái Quốc) created by US MACV’s Special Operations Group (SOG) that operated into North Vietnam – see: VCATT Items No. 24990504001 and 24990501001.

[10] JUSPAO, National Psychological Operations Plan for Vietnam, Guidance Number 20, 12 September 1966 – VCATT Item No. 20580229003. Cited in SGM (Retd) Herbert A. Friedman, PSYOP – Divide and Conquer (psywarrior.com) . See also JUSPAO, Consolidation of JUSPAO Guidance 1 Thru 22, 1 June 1967.

[11] “Leaflet 245-1-67” depicting Mao Tse Tung pushing Hồ Chí Minh – pushing a NVA/VC soldier into an “explosion”. From the collection: SGM (Retd) Herbert A. Friedman, PSYOP – Divide and Conquer (psywarrior.com) .

[12] For comment on “Discord between Northerner and Southerner cadre” by a senior NVA officer who rallied in 1970, see VCATT Item No.11271006005. More generally, see also “North South Divisiveness in the PAVN/PLAF – April 1974” (within the 9th VC Division) – VCATT Item No. 2310513021, and Divisiveness in Communist Ranks, March 1974 – VCATT Item No. 2122902006. Tensions and “lack of cooperation” between “Southerners” and “Northerners” in units – and between the D445 and D440 (previously an NVA unit) Battalions in Phước Tuy Province, were also reported by a rallier – see Appendix II to Annex A to 1 ATF INTSUM No.84/70, Núi Đất, 25 March 1970.

[13] See: The Vietnamese Language and Names, Annex L in Chamberlain, E.P., The Viet Cong 275th Infantry Regiment: To Long Tan and After, 2021. The boundaries of the “three regions” were formalized during the French colonial period – ie the protectorate of Tonkin (northern Vietnam – centred on Hà Nội); the protectorate of Annam (central Vietnam – centred on Huế), and the colony of Cochin China (southern Vietnam – centred on Sài Gòn). In this period, “long, narrow” Annam was the largest – 1,300 km in length, from about 100 km north-west of Sài Gòn and from modern Bình Thuận Province on the coast north to Ninh Bình Province in the North, ie about 100 km south of Hà Nội. The Geneva Accords of mid-1954 divided Annam in about half – along the 17th Parallel, ie into the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).

[14] Central Intelligence Agency – Directorate of Intelligence, Intelligence Memorandum: Politics Within the Communist High Command in South Vietnam, Secret – No. 2105/71, 21 December 1971. Passages redacted.

https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP85T00875R001100100141-9.pdf

[15] Kellen, K., A View of the VC: Elements of cohesion in the enemy camp in 1966-1967, November 1969. 82 pages – prepared for the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense/International Security Affairs. VCATT Item No. 2390516005. For related RAND Corporation studies see “Viet Cong Motivation and Morale”, September 1967 (372 pages). That study noted that “caricaturing or slandering the VC in leaflets is self-defeating.” See: VCATT Item 25590126001; and the late 1966 Quarterly Report at VCATT Item No. 0240603021.

[16] Both the December 1967 and June 1968 directives – with Vietnamese texts, are included in Vietnam Documents and Research Notes, Document Nos. 63-64: “Friction between Northern and Southern Vietnamese: Directives Urge Standing ‘Shoulder-to-Shoulder with our Kith-and Kin Brothers”, September 1968. VCATT Item No. 20580427006. A communist directive in Bình Dương Province similarly cited Northerners “being mocked”, “the butt of jokes by parochialists”, and “being overcharged.” VCATT Item No. F034603600590.

[17] The Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) – directed from Hà Nội and located in the Cambodia/South Vietnam border area north-west of Saigon, was the communists’ political and military headquarters responsible for Vietnam south of the Central and Southern Highlands – an area termed “Nam Bộ” (equating to the French colonial-era “Cochin China” region). Geographically, the COSVN area covered the southern 32 of South Vietnam’s 44 provinces – reportedly containing 14 million of South Vietnam’s total population of 17.5 million (ie about 80%); 53% of its land mass; and 83% of the rice-growing areas (in 1968) – USMACV briefing, Saigon, 9 January 1970 – Sorley, L., Vietnam Chronicles: The Abrams Tapes, 1968-1972 (Modern Southeast Asia Series), Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, 2004, p.336. COSVN however, did not control the area of its “geographic coverage” described above.

[18] B1 Standing Committee, Directive No.84/CV-B1, To All Brothers, 20 December 1967. See also “Frictions Between Northern and Southern Vietnamese, Vietnam Documents and Research Notes No. l 43-44, Saigon, September 1968. VCATT Item No. 213100313. This “B1 Document” – possibly of Military Region 7, was highlighted in the US Mission in Vietnam, Document Nos 43-44, September 1968; that included a second captured “more subtle directive” on a similar theme – dated 2 June 1968, enjoining cadre in the South to “organize a warm reception in order to motivate these troops ((C-category infiltrated Northern recruits)) upon their arrival.” – VCATT Item No. 20580427006. In Vietnamese and English. See that material also reviewed in “Friction Between Northern and Southern Vietnamese”, Vietnam Documents and Research Notes 43-44, September 1968. VCATT Item No. F031300010582.

[19] MACV CDEC Item 112 – Captured by a unit of the US 25th Infantry Division in February 1967. VCATT Item No. 4080121007.

[20] Trương Như Tảng (1923 – 2005), Journal of a Viet Cong, Jonathan Cape, London, 1986, p.159 Tảng – a Southerner, was the PRG Justice Minister. He became disillusioned with the Social Republic of Vietnam post-Liberation – believing that Southerners and former VC were discriminated against. Trương Như Tảng fled Vietnam by boat in August 1978. See also footnote 56.

[21] National Intelligence Center, Interrogation Report, No. 121/67, 14 February 1967. VCATT Item No. F034600422579. See Annex A.

[22] The Northern view of Southerners was that they were: “disloyal, lazy, ostentatious, undisciplined and unorthodox” – see Taylor, K.W., “The Vietnamese Civil War of 1955-1975 in Historical Perspective”, p.27 in Wiest, A and Doidge, M.J., Triumph Revisited – Historians Battle for the Vietnam War, Routledge, New York, 2010. See Chamberlain, E.P., The Viet Cong D440 Battalion, 2013, footnotes 204 and 233. “Homesickness” among troops from North Vietnam was reported by 1 ATF – Annex B to 1 ATF INTSUM No.253/71, 10 September 1971 (see also D440, 2013 footnote 210). Divisiveness in Communist Ranks, March 1974 – VCATT Item No. 2122902006; and for “Divisiveness” and “Disunion” in the 9th VC Division, see VCATT Item No. 2310513021: “The NVN born clan and the SVN born clan. They have conversation time, tea party, banquet separately from each other. They never sit in a common table.”. However, note that some rallier and POW reports can be suspect – eg telling interrogators what ralliers and POW believe would please the interrogators.

[23] Debriefing of NVA Lieutenant Colonel Lê Xuân Chuyển (also known as Thanh Sơn), former A/Chief of Staff and Chief of Operations of the 5th VC Division – who defected in Bình Thuận Province on 2 August 1966.

[24] Chamberlain, E.P., “The Enemy – and Intelligence, in Phuoc Tuy: Successes and Failures” (presentation and paper); Special Forces Conference: Phantoms – Australia’s Secret War in Vietnam, National Vietnam Veterans’ Museum, Phillip Island, 12 April 2014.

[25] Simulmatics Corporation (for the US Army), Improving the Effectiveness of the Chieu Hoi Program, Volume II – The Viet Cong – Organizational, Political, and Psychological Strengths and Weaknesses, Cambridge, September 1967. pp.166-168. VCATT Item No. 25590110001.

[26] JUSPAO, Exploitation of VC Vulnerabilities, Guidance No. 23, Saigon, 14 October 1966, p.3. VCATT Item No. 2171309011.

[27] Simulmatics Corporation (for the US Army), Improving the Effectiveness of the Chieu Hoi Program, Volume II – The Viet Cong – Organizational, Political, and Psychological Strengths and Weaknesses, Cambridge, September 1967. pp.166-168. VCATT Item No. 25590110001. See also footnotes 40 and 41 – total NVA/VC ralliers to 1973 were reportedly “194,000”.

[28] JUSPAO, Exploiting North -South Regionalism Among the Viet Cong – Policy No. 41, Saigon, 3 July 1967. VCATT Items No. 2171312012, 2311706023. For an early US study on “elements of cohesion” in NVA/VC forces, see footnote 14 ie: Kellen, K., A View of the VC: Elements of cohesion in the enemy camp in 1966-1967, November 1969, VCAT Item No. 2390516005.

[29] The National Reconciliation Program – “Đại Đoàn Kết”, was promulgated by the Prime Minister of South Vietnam on 19 April 1967. One of its principal aims was to increase the “rallying” of high and medium-ranking NVA/VC cadre under the Chiêu Hồi Program. Financial inducements offered to hồi chánh (ralliers) included 100,000 piastres (ie equivalent to USD 847) for a regimental commander; 65,000 piastres for a local force battalion commander; and 20,000 for a local force platoon commander. “An important part of the policy is the opportunity of returnees to gain jobs commensurate with their talents and experience.” JUSPAO, Chieu Hoi and Dai Doan Ket National Reconciliation Programs, Policy No. 75, 18 December 1968. VCATT Item No. 2171317020.

[30] Trần Văn Lân was captured on 8 December 1967. His 9th Battalion was in reserve for an attack by the 275th Regiment on the US Special Forces Bù Đốp base at 2200hrs on 7 December 1967. VCATT Item No. F034603101601.

[31] Standing Committee – B1, Directive 84/CV/B1, Bình Dương Province, 20 December 1967. Recovered from a bunker vicinity XT 994431. VCATT Items No. 2131003036 and F034603600590 (CDEC Log 06-1044-68).

[32] Captain Trần Văn Tiểng regrouped to North Vietnam in July 1954, infiltrated into the South: January – May 1965). Tiểng (aka Vẻ, and Sáu Tiểng) was wounded and captured on 26 February 1969 by ARVN forces in Biên Hòa Province – CMIC No. 2550, VCATT Items No. 2310305007 (interrogation – 21 pages).

[33] Appendix II to Annex A to 1 ATF INTSUM No.84/70, Nui Dat, 25 March 1970. On North v South divisiveness, see also footnotes 204, 233 in Chamberlain, E.P., …D440: Their Story, op.cit., 2013.

[34] JUSPAO, Divisiveness in Communist Ranks, March 1974, VCATT Item No. 2122902006.

[35] US MACV/RVNAF, The Disunion Between North and South Elements in the Communist 9th Worksite Division, April 1974. VCATT Item No. No. 2310513021. See the complete text at Annex B.

[36] JUSPAO, Exploitation of Divisiveness in the Ranks of the Viet Cong, Guidance Number 12, 18 December 1965, p.4. VCATT Item No. 2171306026.

[37] United States Information Agency, The Viet Cong: Communist Party and Cadre, Study R-74-66, April 1966, VCATT Items No. 2320808013, 2310113004.

[38] JUSPAO, Exploitation of VC Vulnerabilities, Psyops Policy No. 49, 6 December 1967. VCATT Item No. 2311706020. This paper cited the earlier Simulmatics Corporation study

[39] MACV, Guide for Psychological Operations, 27 April 1968, p.V-10. The Guide also noted: “NVA Personnel In SVN. There is an active program being conducted against the North Vietnamese troops in South Vietnam. This program is designed to create doubts and fears in the minds of the NVA troops. VCATT Item No. 20580213001.

[40] Joint Propaganda Development Centre (RPDC), Division between VC/NVA, Leaflet No. 7-889-69, Requestor – 1st Marine Division, 1969. Also in the Vietnamese language. VCATT Item No. 28530102110. Almost all JPDC leaflets/pamphlets are “Rally Appeals” – very, very few cite the NVA (see however VCATT Item No. 28530105027 to elements of the 2nd NVA Division).

[41] MACV, Friction Between NVA and VC Troops, 17 May 1969, 28 May 1969, 4 June 1969 – VCATT Item No. 2131403110.

[42] This statement is incorrect – see Chamberlain, E.P., … D445 …, op.cit., 2016, Annex G, f.8: “The system included mail to North Vietnam – for detailed regulations on the postal system, see CDEC Log 01-1367-69. On 15 July 1966, Military Region 1 promulgated a Directive on letters between North and South Vietnam, see CDEC Log 08-1555-66.

[43] Sorley, L., Vietnam Chronicles: The Abrams Tapes, 1968-1972 (Modern Southeast Asia Series), Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, 2004, p.261.

[44] MACV, Military Operations – Psychological Operations Policy: Exploitation of Viet Cong (VC) Vulnerabilities, Directive 525-209, 26 January 1970. VCATT Item No. 2171406005.

[45] United States Information Agency, The Viet Cong: Communist Party and Cadre, Study R-74-66, April 1966, VCATT Items No. 2320808013, 2310113004. Begun in 1963, the Chiêu Hồi (“Open Arms”) program encouraged North Vietnamese and Việt Cộng troops and infrastructure members to defect to the Sài Gòn Government. There were reportedly 20,242 ralliers in 1966, and a US “cost-benefit” analysis reported an assessed overall cost of USD 125 for each rallier – that had saved the lives 3,000 “Free World Forces”. Williams, O., Some Salient Facts …, 14 February 1967. “During 1967 only 146 NVA military personnel rallied to the GVN of an estimated total of 54,000 NVA personnel serving in all-NVA units and another estimated 7,000 assigned as fillers in VC main and local units.” See also: The NVA Soldier in South Vietnam as PSYOP Target, PSYOPS Policy No.59, 20 February 1968, VCATT Item No. 2171316009. For a 1973 study of the program, see: See also Koch, J.A., The Chieu Hoi Program in South Vietnam 1963-1971, Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, January 1973 (223 pages). At p.10, Koch notes: “Few high-ranking Viet Cong and fewer NVA have rallied.” A “breakdown of Hoi Chanh by Category” (pp.11-12) notes that in the period 1967-1971, 85,544 “VC Military” rallied and 1,108 “NVA Military” rallied. In the same period, 42,356 “Political” rallied and 16,286 “Others” rallied. The “Others” category included: “dissidents, followers, draft dodger, deserters, porters etc who actively supported the VC.” A “break-down” of VC/NVA for 1965 and 1966 was “not available”. See: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2006/R1172.pdf.

For Chiêu Hồi statistics for all provinces – see VCATT Item No. 2234403020.

[46] Saigon Sees Northerner-Southerner Conflict in the NLFSV, Saigon Domestic Service, 14 August 1973. VCATT Item No. 2310702009.

[47] The author (Chamberlain) has reviewed several hundred US and South Vietnamese psychological warfare pamphlets, leaflets and posters targeting the NVA/VC – including in the works of Herbert A. Friedman – PSYOP – Divide and Conquer (psywarrior.com). To date, no document illustrating VC versus NVA tensions etc has been noted. Note also the preceding US study at footnote 15 that included: “caricaturing or slandering the VC in leaflets is self-defeating.”

[48] Pentagon Papers – Book 2, Part IV.A. History of South Vietnam 1954-60: Hanoi and its Relationship to the Insurgency in the South, p.40. VCAT Item 2321618002.

[49] In Phước Tuy Province, Bình Giã village was founded in November 1955 – with 2,100 Catholic refugees from Nghệ An (North Vietnam) following the 1954 Geneva Accords. The population of Bình Giã village in 1964 was 5,726 – of whom 90 percent were Catholic refugees The villagers of Phước Tỉnh village were also almost all Catholic – principally comprising refugees from the North. In 1970, its population was 10,697 in four hamlets.

[50] Trần Văn Trà – Colonel General (1918-1996) was born in Quảng Ngãi Province (Central Vietnam ie Annam – ie post-1954 within the Republic of Vietnam. Post-War, General Trà wrote The History of the Bulwark B2 Theater, Volume 5, Concluding the 30-Years War. 2 Feb 83, VCATT 28810605001. The account offended and embarrassed the leaders of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, and he was purged from the Politburo. Note also the “Southerner” Lê Duẩn (1907-1986) – the General Secretary of the Vietnam Workers’ (Lao Động) Party from 1960, was also born in Quảng Ngãi, and successfully promoted Resolution 15 that sanctioned armed force in the South despite the resistance from the “North-first” moderates in the Party. See pp.43-44 in: Nguyen, Lien-Hang T., Hanoi’s War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2012.

[51] The CIA report added “Thus, countrywide, 46 of the 58 known enemy regiments are completely North Vietnamese, and nine of the 12 Viet Cong regiments are believed to be 50% North Vietnamese.” CIA, Research Memorandum: Increasing Role of North Vietnamese in Viet Cong Units, 17 September 1968. VCATT Item No. F029200060548.

[52] CDEC Log 10-1719-69.

[53] Hanoi Still Denying Presence in the South, December 1968. VCATT Item No. 2310615051 – also 2310614045.

[54] Infiltration Pass – “Corporal” Phạm Trường Yên: born in Ninh Bình Province, recruited into NVA/PAVN on 2 July 1965, began infiltration on 14 December 1967 through southern North Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, South Vietnam. On arrival in the South,Yên was allocated to 2nd Battalion of the 275th Regiment in Tây Ninh Province on 4 May 1968 and engaged in his first battle in South Vietnam on 23 May 1968. He was killed-in-action by elements of the US 101st Airborne Division in the vicinity of XT 4923 on 30 June 1968. Yên’s captured notebook recording his service is detailed and legible. VCATT Item No. F034603861484.

[55] US Embassy – Saigon, Assessment of Communist Strategy – June 1974. VCATT Item No. 2122907004.

[56] In 2016, a 205th Regiment veteran published a short history of the 5th Regiment and the 205th Regiment on the Internet – Trần Đức Lộc, “E 205 Miền Đông Nam Bộ” (“The 205th Regiment in the Eastern Nam Bộ Region”), 2 January 2016. He noted that “the Regiment had many different titles: the 1st Regiment, the 5th Regiment, and the 205th Regiment. … The Regiment had suffered 4,860 of our comrades killed – including 890 killed in Cambodia, apart from those who were wounded.”

https://www.facebook.com/groups/184221888598381/permalink/494503990903501/ .

[57] Chamberlain, E.P., The 33rd Regiment – North Vietnamese Army: Their Story (and the Battle of Binh Ba), Point Lonsdale, 2014, pp.66-84. Chamberlain, E.P., Vietnam War: The Battle of Binh Ba – June 1969: Enemy Aspects, Research Note 9/2019, 13 May 2019.

[58] The Châu Đức District History related the attack by the 33rd NVA Regiment at Bình Ba and the attack by C-41 on Hòa Long (led by its commander Nguyễn Thanh Đằng) – p.143, p.147. Lê Minh Đức and Hồ Song Quỳnh (ed), Lịch Sử Lực Lượng Vũ Trang Huyện Châu Đức (1945 – 2014), NXB Chính Trị Quốc Gia – Sự Thật, Hà Nội, 2014. Unpublished English translation by E.P. Chamberlain.

[59] Trương Như Tảng, Journal of a Viet Cong, op.cit., 1986, pp.264-270. Tảng – the PRG Justice Minister, fled Vietnam by boat in August 1978. See also footnote 20. For post-War disillusionment, see also: Bùi Tín, Following Ho Chi Minh, Crawford Publishing, Bathurst, 1995, pp.90-111, p.142: NVA Colonel Bùi Tín “defected” in France in late 1990.